Advertising campaigns had a great impact on Black American Communities and culture in the 1990s. Advertisements influenced 90’s politics, community health conditions, standards of beauty, technology, and countless other aspects of Black life. Holistically covering the impacts of such campaigns would likely require a novelistic thesis rather than a blog post. But in this writing, I will briefly cover some of the 90’s marketing/advertising campaigns that greatly impacted Black Americans. This is no attempt to capture everything, but rather a start; one that should be built upon over time.

Advertising campaigns had a great impact on Black American Communities and culture in the 1990s. Advertisements influenced 90’s politics, community health conditions, standards of beauty, technology, and countless other aspects of Black life. Holistically covering the impacts of such campaigns would likely require a novelistic thesis rather than a blog post. But in this writing, I will briefly cover some of the 90’s marketing/advertising campaigns that greatly impacted Black Americans. This is no attempt to capture everything, but rather a start; one that should be built upon over time.

- George H.W. Bush’s “Revolving Door”

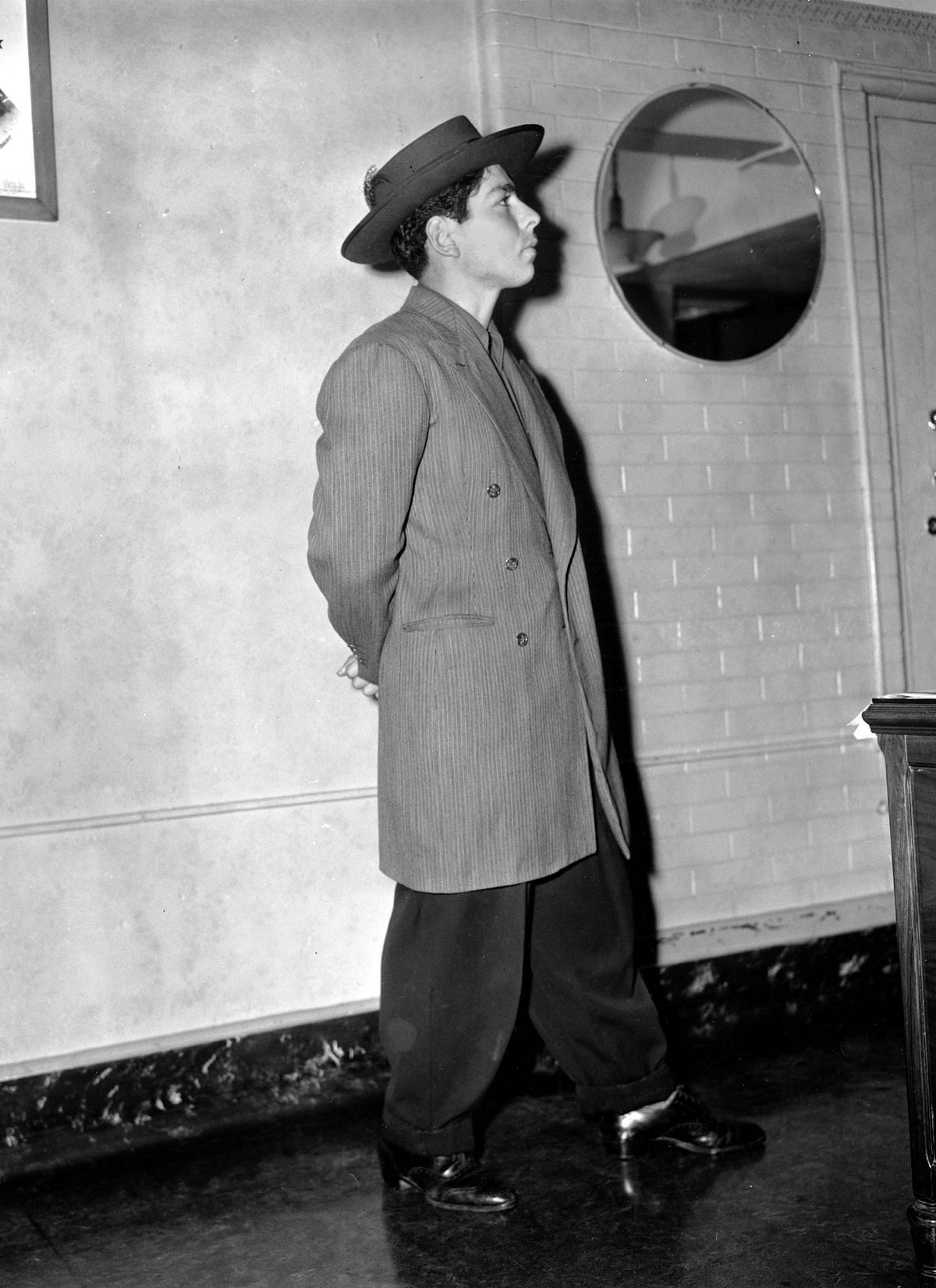

George H.W. Bush’s “Revolving Door” advertisement was released in 1988 but had a large impact on the “tough on crime” initiatives that would drive many of the legal policies that increased levels of mass incarceration in the 1990’s [it’s almost needless to say that a disproportionate number of those legally affected were/are people with black and brown skin]. The ad attacked a prison weekend furlough program that had been supported by George H.W. Bush’s Democratic presidential challenger, Michael Dukakis, when Dukakis was governor of Massachusetts. The ad a focus was placed on a specific case/instance that terrified white America: The story of Willie Horton, a Massachusetts state prison inmate (and a dark-skinned African American male), who raped a woman while on a weekend furlough. The Ad successfully struck a major blow to Dukakis’ campaign, contributing to Bush winning 80 percent of the electoral vote. Bush successfully won his campaign, while also intensifying American race relations in a way that came with grave consequences for American minorities.

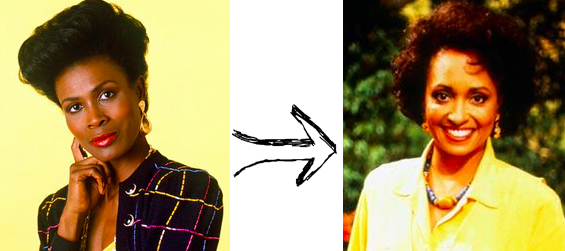

2. Nami Campbell and Gianni Versace

According to surveys conducted in the 1990’s, African-Americans were included in roughly 11 percent of all advertisements. However, Black People were most often depicted in minor, degrading, or background roles rather than prominent major roles. In 1991 Nami Campbell began making advertisements for Gianni Versace. This was revolutionary at the time because her representation pushed against notions that Black women didn’t have the ability to front international fashion brands… well, at least depending on one’s perspective. Though she was a dark-skinned Black woman, Nami Campbell still upheld other White/European standards of beauty: such as wearing synthetic long silky hair. One could argue that even in the midst of modeling with dark skin, she still perpetuated long-standing biased notions of beauty.

3) Mcdonalds Focused Heavily on Black Communities

During the 1990’s McDonalds targeted Black communities very heavily. One of the most memorable Advertising campaigns run by McDonalds in 1990 and 1992 have come to be known as the “Calvin’s got a job” ads. In the ads McDonalds used the story of and African American character named Calvin to display the social mobility potential of working at McDonalds. The ads even went as far as to imply that Calvin may become the owner of the restaurant one day if he kept working hard. Such campaigning focused towards Black communities positioned McDonald to look like assets in Black communities, rather than liabilities that were contributing to problems and capitalizing on their struggles. Zak Cheney-Rice from Mic.com wrote that “Mickey D’s efforts to highlight investment in the black community seem starkly in opposition to the rate at which they flood these same communities with extremely unhealthy food. This inevitably contributes to a slew of health issues, from heart disease in adults to ‘skyrocketing’ diabetes rates in children.”

4) Brown Tobacco and Brown Hands

“We don’t smoke that s_ _ _. We just sell it. We reserve the right to smoke for the young, the poor, the black and stupid.” ―R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company Executive (1992).

According to Connolly, G.N.’s essay “Sweeet and Spicy Flavours: Brands for Minorities and Youth”, during the period of 1995-1999, tobacco companies sponsored at least 2,733 programs, events, and organizations throughout the U.S, equaling a bare minimum of $365.4 million spent on such sponsorships alone. Many of the sponsorships consisted of small community-based organizations in Black and Minority Neighborhoods. Furthermore, studies from 1990-1998 found that there were 2.6 times as many tobacco advertisements per person in areas with an African American majority compared to white-majority areas. During this period, menthol cigarettes became a staple in Black American culture, becoming the cultural preference.

Let us know what Advertisement/marketing campaigns come to your mind when you think about the 90’s (comment below).

For example, dashikis and afros were seen as signs of defiance and militancy in the 1970s, as many Black Americans backlashed against American norms. Perhaps sagging pants came to popularity in the 1990’s, out of urban youth’s desire to defy social norms and expectations. Perhaps people began empowering themselves with sagging pants by blatantly rejecting the control of mainstream American society… A society that they felt would never fully grant them acceptance; so they stopped striving for the acceptance and worked to make it clear that there was no longer a care for mainstream approval… Perhaps.

For example, dashikis and afros were seen as signs of defiance and militancy in the 1970s, as many Black Americans backlashed against American norms. Perhaps sagging pants came to popularity in the 1990’s, out of urban youth’s desire to defy social norms and expectations. Perhaps people began empowering themselves with sagging pants by blatantly rejecting the control of mainstream American society… A society that they felt would never fully grant them acceptance; so they stopped striving for the acceptance and worked to make it clear that there was no longer a care for mainstream approval… Perhaps.