Note: I have tried to keep this entry spoiler-free, so as not to discourage those who haven’t seen Mississippi Masala from finally watching this slightly-cheesy but lovingly-made film. It’s worth a watch if only because it’s one of the few films of that era (well, probably even now) that does not feature any main characters who are white: enjoy this large serving of melanin with a cup of spicy chai. But not that shit from the coffee conglomerate down the street. Warning: only one in ten American “chai” lattes is actually anything close to authentic chai.

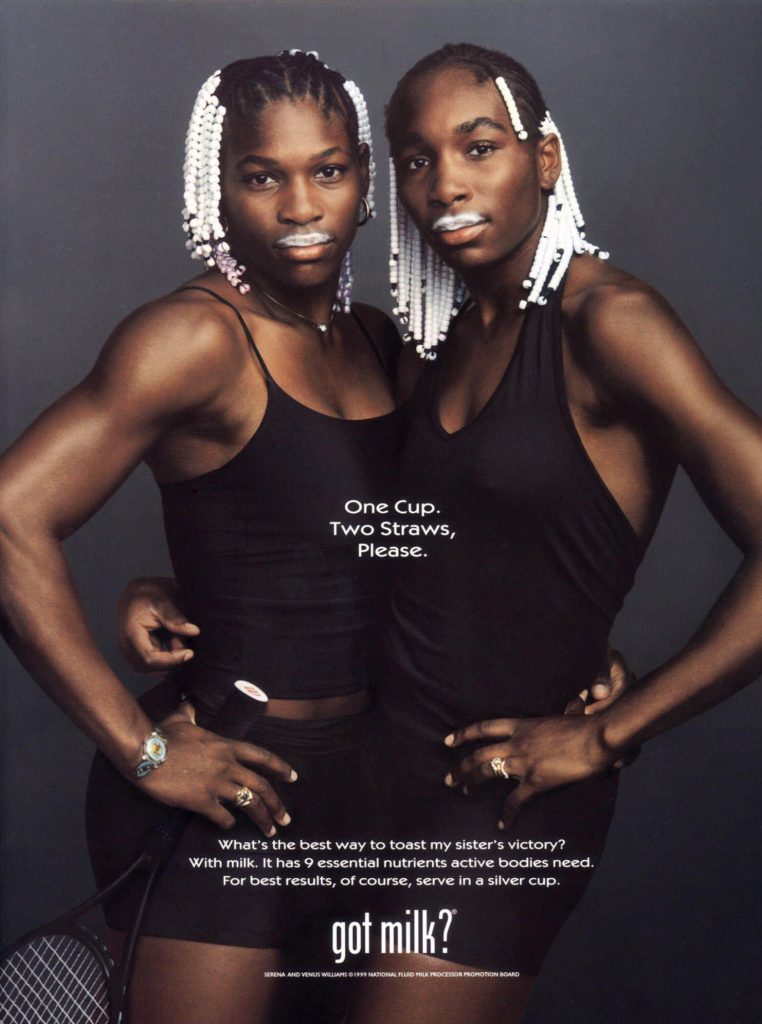

The immigrants’-child-American-citizen experience that’s been successfully mined in shows like Master of None and Fresh Off the Boat made one of its first appearances in America when Mira Nair’s Mississippi Masala hit screens in 1992.

Nair was born in 1957 to a Punjabi couple in India. Her father was a civil servant, so Mira and her family moved several times, and Mira herself later lived in several different places including the United States and Uganda.

(A Young Mira Nair)

As its title suggests, Mississippi Masala takes place in the southern state of Mississippi, a prominent part of the notoriously conservative Bible belt, still glowing with ghosts of its dark plantation slavery past.

My dad came to Atlanta, another of the South’s treasured gems, in the late 1970s after the city played a significant role in the Civil Rights Movements of the 60’s. He had friends who were attending Georgia Tech, and he attended Atlanta University to earn a Master’s in Business. He was heavily influenced by the blaxploitation films of the era, but, honestly, a lot of men, especially men of color, had gone all in on the macho magnetism of Richard Roundtree and carefully trimmed and greased their hair into Imitation Afros and thick, porkchop sideburns. It was a look they could actually recreate, and their plaid bell-bottoms and leather jackets completed the look in a comically dashing, or maybe dashingly comic, way. My dad seemed to absorb qualities of the black and white men he came to know, while honing his best Indian self with his friend family of other South Indian immigrants. He loved to listen to his folk and film songs from India, but he also sang along to Lou Rawls and Dolly Parton – he still loves the chorus of “Jolene.”

When Indian immigrants found each other, they tended to stick together, teaching each other where to find the right spices for their home-cooked food and how to do laundry and clean their homes – things they were never asked to do in India, where mothers, maids, sisters — basically, women — handled those chores for them. The wives they brought over also faced several firsts together, and, together, they learned how to pay mortgages, buy cars, get loans, attend universities. Their still-thick accents and obviously-ethnic looks might have alienated them from mainstream America, but they found comfort in each other and the warmth of Americans who did want to learn about another culture: one rich with tastes, traditions, and stories that their new brown friends were so eager to share with them in an effort to keep their memories of home safe from erasure. Immigration led to both situational hybridity (the forced mixing seen in public transit, schools, neighborhoods) and organic hybridity (the sharing that occurred wherever people eventually figured out how to work, learn, and live alongside each other, picking up bits and pieces of each other’s cultures until they formed a mosaic created by thousands of fine pieces).

Not everyone got along so harmoniously, though. In America and beyond, people of color, who had been displaced and dispersed throughout the world during the Imperialist Era, sometimes found it extremely difficult to collaborate, not compete, with each other.

East African countries and India share an extensive history, especially in regard to the trade they conducted via the Indian Ocean. (Some research even suggests that the roots of Rastafarianism can be found in ancient Hindu worship of Lord Shiva – a dark-skinned lord with matted, dreadlocked hair whose rishis, intense devotees, seemed to feel closest to Him while experiencing the highs of ganja, also known as marijuana – but that’s a different entry for a different sort of platform.)

However, some Indian immigrants of the 70’s wave arrived as exiles after Idi Amin commanded them to leave Uganda, indicting them for earning a disproportionate amount of money while native Ugandans struggled to compete – an echo of anti-immigrant sentiments which were also rising in America. Though the most vocal opponents of immigration were usually white, many black and brown Americans were also seeing such different faces for the first time, and the immigrants brought their own prejudices about skin color, class, and “appropriate” behavior from back home.

My personal experience with race-mixing was closer to that of the protagonist of Mississippi Masala. (Though, sadly, I did not fall in love with a handsomely adorable young black man with a blue-collar job and gold-colored heart.)

I grew up first in Atlanta, then Columbus, GA, attended a predominantly white Judeo-Christian private school, and spent too many years looking like Steve Urkel wearing one of Blossom’s or Brandy’s hats. There were about 15-20 Indian-American kids in my school, a smattering of Asian and Latino kids, and a few black students. My childhood was filled with Indian culture. My dad is a storyteller at heart, a master of voices and comic timing who thrilled me with Indian folktales and memories of his family’s village.

My parents loved to host large music parties during which they and their friends (The Greencard Fellowship, if you will) brought their instruments and sang, danced, and played cards well into the wee hours of the morning. My mother loved classical Indian music and dance; she enrolled me in Bharatha Natyam classes when I was four and became my dance mom and makeup artist for the next twenty years. My grandmother loved to knit and sew, and she was my source for Hindu mythology. My mother loved pointing out how “new trends” in America, like recycling or organic food or yoga, were old hat or common practice already in India. “Water conservation? India has been conserving water for centuries. Even in my house, we kept the cold water in a big well, and we’d only heat up whatever we needed for our bath, and we used to mix the hot and cold water in a bucket and use a big cup to pour the water. These showers you love so much waste so much water.” Then she’d passive-aggressively add “India did it first” in the same tone all moms use whenever they decide to eventually tell you “I told you so” before smiling smugly and returning to their Reader’s Digests.

All of this kept me deeply rooted in my culture even while I (unsuccessfully) wore Hammer pants, listened to Michael Jackson’s Bad while dancing in the kitchen with my mom, and, later, rapped along with Coolio. (Yes, Coolio. At least I’m brave enough to admit it, unlike y’all in the back who are chuckling. Stop. You know what you did. All of us 90’s Kids know, deep down inside, just like we all secretly know the lyrics to “Ice, Ice Baby.”)

Unlike Mina, one of MM’s main characters, I’ve been fortunate enough to travel to India several times. During the 90’s, when India was largely still healing from the devastating effects of the British Empire’s cruel reign, going there was neither the romanticized nor poverty-porn experience we’d come to associate with Exotic India, and while I felt connected to my supposed “homeland” though I was here in America, it was very easy to feel like the outsider I was once I was actually there.

In America, I felt most comfortable with other girls of color, and one of my best friends was (and still is!) the daughter of an immigrant from Nigeria, and I’ve recently realized how much of the “second-generation” experience we shared together. However, underneath these fun cultural exchanges and communities of support were also racist sentiments, which went mostly unaddressed in any significant way.

Sadly, whether the stereotyping and subtle fear of other cultures and colors was (a) the product of hatred deliberately spread and managed by the British Empire in an attempt to prevent Indian people from rising together to defeat them, (b) beliefs they heard at home in India, (c) paranoia they felt as strangers in a new country, or (d) naivete in the face of caricatures they saw on TV and heard in a language they didn’t fully understand, some of our parents’ private conversations about politics or religion sometimes carried tinges of racism that were never mentioned outside the home. Once my fellow second-gens started going to college, we realized that many Hindu parents raised their kids with almost the same set of rules: never score less than a 99 on any test, never forget the name of a relative (especially one in India), and never bring home a romantic partner – oh, and also, never, never come home if you are discovered with one who is White, Black, or Muslim. They eventually caved on the White thing, but the doors to the others remained firmly shut.

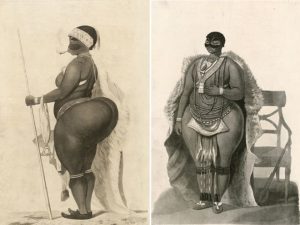

Radharani Ray’s article describes the kind of racism we saw within the Indian community and other immigrant groups. For one, colorism runs deep in Indian culture, as it does in most non-white ones. Women cover their faces and stay out of the sun in order to avoid becoming dark, store shelves are stacked full of skin lightening products, and families hope and pray for fair-skinned children and grandchildren, as dark skin can sometimes ruin job and marriage prospects. This fear of The Dark — perhaps another damaging effect of Imperialist propaganda meant to demean and divide native citizens — might have influenced the way some Indian immigrants interacted with (or avoided) other people of color.

At other times, these tensions more resembled classism, one serving as a coded cover for the other. Some immigrants from India came from middle-class or wealthy families and never told their loved ones back home that they worked part-time in restaurants or big box stores to supplement their meagre student allowances; other ones scrimped and saved to collect the funds to finally come to America, but once they invested what little they had in founding small business and motels, they moved up the class chain and sent as much money as they could back home. In time, like the Indians who fled Uganda, some Indian immigrants in America faced resentment from other non-white groups that were still struggling hard to achieve their American dreams, and some of those successful immigrants felt uncomfortable speaking out against racism for fear of alienating white people who they now worked with and for – they didn’t want to lose the newfound American-ness they worked so hard to develop, and they didn’t want to lose the security of the paychecks they worked so hard to earn after climbing out of abject poverty without running water or lights at home. At times, they falsely believed that their financial success was proof of their superiority over others. generally, whenever different non-white races collided, they seemed to silently acknowledge the cutthroat competition they were all lodged in, trying to climb closest to “White” or “Success,” which was still largely defined as “White” in the 90’s.

The conflicts in Mississippi Masala are reflective of this not-so-subtle “Fine, I’m not winning, but I’m not losing as badly as you are” attitude. Who’s always suing whom, who is racist despite being only a couple of shades lighter than the other, who can’t be trusted — these are questions that swirl around in the film’s dialogues, and the conclusion seems to be that a genuine connection is what truly defines a relationship between two people or a person and a place.

Mississippi Masala – Racial Tensions

Mira and Demetrius fall in love because they shared senses of humor, interests, similar relationships with their families, and desires to find something bigger than themselves and/or Mississippi. Kum-Kum Bhavnani notes bell hooks’s and Anuradha Dingwaney’s criticisms of the film, which focus on its oversimplification of the race issue: “love conquers all” is an empty cry when followed by a reminder of the bloody lynchings and the savage institution of slavery which occurred in Mississippi and abroad as a result of racist beliefs and practices. This movie makes an unrevolutionary, mostly sentimental statement. But the narratives of Mississippi Masala’s Jai and Mina show, however, that racial identity is ambiguous, since Jai says that despite his Indian birth he feels most at home in Uganda, and Mina reminds her parents that she is not Indian but American, and class and race aren’t supposed to matter in America (Ray 171-2). When her mother explains that she and Mina’s dad are supposed to look out for their daughter, she adds a question loaded with fear a few immigrants felt about trusting “others” in a strange country away from the careful eyes of extended family and people with seemingly similar values: “if we don’t, who will?”

Mississippi Masala – Mina’s Complex Identity

Br

Bringing America, India, and Uganda together highlights the reality Paul Gilroy brought attention to in Black Atlantic: that non-white cultures have always been tied together and existed in both situational and organic hybridity. The issue of assimilation, though, remained. The 90’s was a decade of figuring out where these lines and boundaries between our separate worlds exist, and how, or if, they should be broken down or replaced with new ones. When I started going to school in Columbus with other Indian-American kids, I watched some of them keep the “Indian” part of “Indian-American” under wraps with ethnically ambiguous names like Neil, Nina, Jay. Over the years, we gradually became more confident sharing the other half of our identities with our classmates, but oddly enough, though we hung out often outside of school, we lived fairly separate lives at school so as not to seem like we were deliberately clumping together.

Meanwhile, in the early 2000’s, Bobby Jindal’s brief success in post-Katrina New Orleans seemed like evidence of this romantic notion of assimilation, but a closer look at his personal history reveals another reality that’s just as complex as the first: “Bobby” was born Piyush Jindal before he officially changed his name to match the youngest Brady boy (no, really), converted from Hinduism to Catholicism, and said, when he and his wife were asked if they kept up with any Indian traditions in their home, some version of “No, we’ve been raised as Americans. We do American things like other Americans who love America like we do since we’re all Americans.” I have vivid memories around that same time of attending a small rally for another Indian-American political candidate who claimed that even though he looked different, he was just as Southern as anyone else in that room on Georgia Tech campus; he even had a coon dog and a white wife. (Surprise!)

So, assimilate or separate? Play the game or create our own new games?

Mississippi Masala was less an answer to those questions and more a presentation of those questions on both smaller and larger scales (a small town in Mississippi, a small town in Uganda, and both cities sort of transferred onto those transparency sheets our teachers still used back then and laid on top of each other to show how those cities fit into the larger diaspora) and for its viewers’ consideration. In the 90’s, viewers of color saw themselves featured centrally in a film, and some white viewers saw Mina and other Indian faces for the first time, at least outside of a restaurant, a motel, or The Simpsons.

Thanks to Mira Nair, Americans, new and old, had at least some alternatives to Apu.

— Radhika Nataraj

Works Cited

Bejarano, Christina, Gary Segura. “What Goes Around, Comes Around: Race, Blowback, and the Louisiana Elections of 2002 and 2003.” Political Research Quarterly, vol. 60, no. 2, pp. 328-37.

Bhavani, Kum-Kum. “Organic Hybridity or Commodification of Hybridity? Comments on Mississippi Masala. Meridians, vol. 1, no. 1, 2000, pp. 187-203.

Desai, Gaurav. “Oceans Connect: The Indian Ocean and African Identities.” PMLA, vol. 125, no. 3, 2010, pp. 713-20.

Ray, Radharani. “Interrogating Race in Mississippi Masala.” Race, Gender, & Class. vol. 8, no. 4, 2001, pp. 155-75.

Taylor, Ian. “India’s Rise in Africa.” International Affairs, vol. 88, no. 4, 2012, pp. 779-98.