Background, God’s Property:

God’s Property, founded in 1992 in Dallas, Texas, was developed by Linda Ray Hall-Searight, a public-school music teacher, and her son, Robert Sput Searight, who has since gone on to become a world-class drummer and Grammy Award Winner. The original ensemble included more than fifty singers and a band of approximately twenty musicians, recruited mostly from Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing and Visual Arts High School (where other notable alumni such as Erykah Badu, Willie Hutch, and Roy Anthony Hargrove also attended[1].)

In 1993 the choir collaborated with Kirt Franklin, providing backup vocals for his 1995 album Whatcha Lookin’ 4. In turn, Franklin appeared on and helped produce the group’s debut album, God’s Property from Kirk Franklin’s Nu Nation, released May 27, 1997. The album won the NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Gospel Artist, the NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Music Video, the Soul Train Music Award for Best Gospel Album, and the Grammy Award for Best Gospel Choir or Chorus Album in 1998. The album was #1 on the R&B Albums chart for 5 weeks, #3 on Pop Charts, and would go on to be certified triple platinum with over 3 million copies sold across the United States[2]. The lead single “Stomp”, featuring Cheryl “Salt” James (of Salt-N-Pepa), made it onto Hot 100 Airplay, Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Airplay, Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Recurrent Airplay, Rhythmic Top 40, The Billboard Hot 100, and Top 40 Mainstream[3].

Interview with L. Nyrobi N. Moss:

CECILY: Hello, this is Cecily McMillan of writing for Professor Scott Heath’s course: Archiving the Black 90’s. I am attempting a new way at archiving the black nineties by speaking to a Ms. L. Nyrobi N. Moss, who was a foundational and central member to the musical group, the musical phenomena: God’s property, that pretty much developed the genre of Urban Contemporary Gospel. In which way did you find a path to participate in the arts and the music of the nineties?

NYROBI: So, I went to performing arts high school, I also went to performing arts junior high school as well, but my interest in the entertainment industry came via arts magnet, which was a breeding ground for a lot of major artists, but a lot of creative expression in Dallas and, essentially, spreading to the world. So, in addition to attending arts magnet, I also was one of the original founding members of the choir called God’s Property Ensemble and God’s Property was of course released under Kirk Franklin’s label in 1997. However, before that release, we already had a really huge following in the Dallas, Houston, L.A., and a lot of different markets as far as Gospel groups were concerned, and that also kind of led us to work with other artists and playing with different background vocals and singing on other people’s tracks. But we were also signed by B-Rite, a division of Interscope, so Tupac Shakur was one of my label mates. So that is my introduction to the nineties in music.

CECILY: You said that album popped off, like, the group was signed by the label in ’97?

NYROBI: No, we were assigned before 97. The album got released in 97. So, the first full album was God’s Property with Kirk Franklin’s The Nu Nation. However, I want to note that we were God’s Property before Kirk Franklin was Kirk Franklin, and I know because I sang on his first album. But, either way, you know, it was the terminology of who gets picked up first in the industry versus who releases whom. So, at the time he had the platform and he did a lot of producing on our first album when we worked with him.

CECILY: OK. So, 1997. You’re in high school?

NYROBI: No, I was way out of high school. But God’s Property started when I was [at Booker T. Washington] high school. We first formed God’s property, I want to say in ’93-’94.

CECILY: Booker T. Washington, was it a racially diverse high school?

NYROBI: Booker T. Washington for the Performing and Visual Arts was racially diverse. It was culturally diverse, religiously diverse. Some of my best friends were, you know, satanists and had shaved heads, and we all were just these artists that lacked on things, but we didn’t have a problem just crossing over and figuring out who was what. You know, at Booker T. you could see all these different genres in silos and nobody really was kind of singled out. It was just like, you got your group of those who are visual artists and those are the vocals. And those were the hip-hop kids and, so, the music tied us all together.

CECILY: So, I’m thinking about the form of music that you’re talking about. And obviously there are songs, especially in the nineties, I mean the first one that comes to mind for me obviously as Madonna, Like a Prayer. But the incorporation of Gospel into songs, especially ballads, is a super powerful mechanism. Did that become popular in the ’90s?

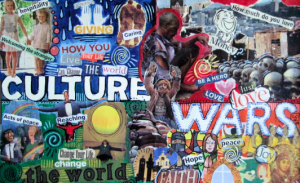

NYROBI: I want to be clear: It wasn’t about incorporating Gospel. Gospel is pretty much the root. If you find any artist, especially black artists, they’re going to tell you their group got started in Gospel. The reason why God’s Property was so pivotal was because we were young, and we were fun and we were hip and we used to bring, you know, rap melodies [into the music]. Like when I was in junior high school, I played classical piano and I hated every minute of it, which is why I switched over to theater, musical theater, because it was boring. So, God’s Property was the first time that I knew that music could be fun and that it could be interesting, and it could have a great high energy. And Gospel, in turn, like we used to bring down houses and churches. Our biggest criticism was the fact that, you know, that we were singing devil songs and we were jamming to Gospel music. And we were doing that in church, and we brought such high energy to it, and, you know, we were too radical. So, people couldn’t tell the difference between what our music was and what Gospel was and that was a problem. Now it’s old hat. Now, you can find you all these different Gospel artists and they all hip-hop, and this and that and the third. But that wasn’t done then, you know. We used to get a lot of flack for that.

CECILY: Yeah, I could see that on the church side. But also, thinking about myself as a teenager, it seems totally incomprehensible that I would get together with a group of my friends and want to do something Gospel inspired. So, I’m clearly missing a link here. How did this emerge?

NYROBI: They’re all linked. The interesting thing is that R&B, hip-hop, they all have roots in Gospel. If you ask any artist where they came up, where they got their musical influences, then they’re gonna say in the church. So, the thing about that is that church, especially in the black community, always influences where we are socially, where we are politically, you know, how we build movements, what that looks like. So, I will say that it wasn’t far removed from us because we used to be in a church doing jam sessions. And even jazz, which is one of the greatest art forms ever because it has these different musicians that’s riffing, that’s doing all this other kind of improvisational stuff. All those things were not removed from us. They were all part of who you were. And so, therefore, we were young. We lived, we loved, we lived hip-hop. We lived where hip-hop started, what it was all about, know what I’m saying? In the nineties, we had your 2 Live Crews and different artists… when hip-hop was kind of risqué. But where we were and where we sat was in this place where it was all creation, it was all music for us. We blended all this together and they weren’t separate for us.

Works Cited

[1] Wikipedia – Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing and Visual Arts