You should never argue about religion, politics, and…umm… sagging pants. The 1990’s gave rise to many fashion trends, but sagging pants has stood as one of the most controversial. People have argued over the historical roots, the psychology behind people showing their behind (slight word-play pun intended), and there have even been instances of people pushing to ban sagging pants altogether. “Which movie was better: Friday or Boyz n the Hood?”, “Who had a bigger impact: Biggie or 2pac?”, “Did O.J. really do it?”, and “Why did many people in urban areas begin sagging their pants?” are all topics that universal scholars and barbershop clients could endlessly debate.

You should never argue about religion, politics, and…umm… sagging pants. The 1990’s gave rise to many fashion trends, but sagging pants has stood as one of the most controversial. People have argued over the historical roots, the psychology behind people showing their behind (slight word-play pun intended), and there have even been instances of people pushing to ban sagging pants altogether. “Which movie was better: Friday or Boyz n the Hood?”, “Who had a bigger impact: Biggie or 2pac?”, “Did O.J. really do it?”, and “Why did many people in urban areas begin sagging their pants?” are all topics that universal scholars and barbershop clients could endlessly debate.

One popular narrative regarding the rise of sagging pants in the 90’s is that prison fashion trickled over to everyday fashion worn in the street(s).This argument has grounds because between the years 1990-2000, U.S. prison rates grew from roughly 800,000 to 1,400,000. Prison populations aren’t allowed to wear belts and are often provided with oversized clothes. Many believe that such prison clothing distribution practices led to a normalization of sagging pants; one that ex-prisoners did not abandon upon being released back into their personal communities. Furthermore, about a decade before the 90’s, various influential sources, such as the Washington Post, began publishing articles declaring that “Prison Has Become ‘Rite of Passage’”. If such a theory is true, then it may strengthen the arguments of those who believe that sagging pants originated in prison; if prison is a rite of passage (for at least some groups or individuals), then quite naturally various people would lean towards dressing as if they’ve been imprisoned.

There’s also a separate prison origin-based belief, that accredits the initial act of prisoners sagging their pants to sexuality, rather than a sheer lack of belts and better clothing. A commonly perpetuated idea has been that prisoners began showing their behind in order to advertise sexual availability. It has also been said that certain prisoners were forced to wear their pants below the waist in order to communicate to other prisoners that they were taken (“taken” as in concurred/controlled by another inmate). Though such narratives are popular, like the Big Bang theory, their accuracy has yet to be completely confirmed.

Stepping away from the prison narrative, some argue that the trend of sagging pants that rose in the 1990’s was simply a result of young people in urban communities trying to maneuver poverty: children and teenagers tend to have many growth-spurts, and in the midst of economic struggles, continuously buying clothes for growing children can quickly become costly. A solution implemented by many parents and young shoppers was to buy clothes that were too big, so that the intended wearer would have an opportunity to grow into them over time (a practice that is still very common). due to many families struggle in urban communities, purchasing belts were sometimes viewed as a luxury, rather than a necessity. Some people believe that the two factors (oversized clothing and not being able to afford belts) led to the trend of urban youth unapologetically wearing baggy pants that hung below their waistline.

Though as human beings we tend to search for simple explanations, the reality is that few things are black and white, and it’s possible that all the arguments/narratives above may hold some level truth. But to shake up the conversation a bit, if the saying “there’s nothing new under the sun” holds any validity, then potentially the most accurate answer regarding the roots and psychology behind the birth of sagging pants in the 90’s can be discovered through exploring eras prior to the decade.

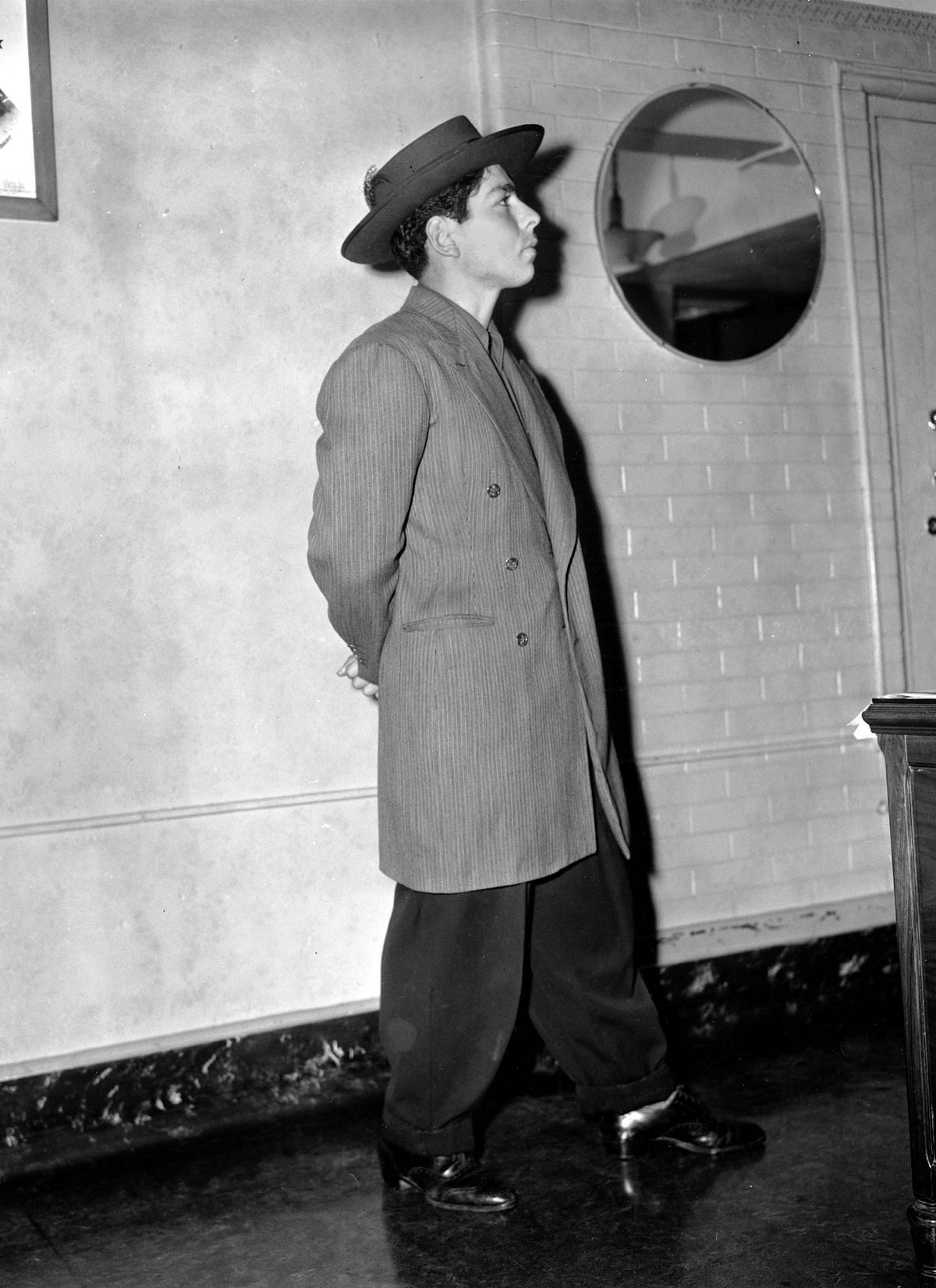

Historian Luis Alvarez states that zoot suits of the 1930s and 1940 “share much of the same DNA as the trend of sagging pants that gained popularity in the 1990’s. Zoot suits were baggy, worn by youth in urban spaces and associated with criminal activity by Black and Latino people.” The suits were initially worn in such a way due to people not being able to afford fitted suits and was eventually adopted as an intentional style linked to Jazz music. Sagging pants started out being worn by youth in urban spaces and was/is associated with criminal activity by Black and Latino people. Also, the affordability and mainstream music adoption aspect has perpetuated the popularity of the style as well. One important thing to note about the zoot suit wearers is that, for them, the style represented a form of moral and political defiance. Luis Alvarez states that zoot suits were “ways that people made statements about their relationships to other people and their circumstances”. A majority of narratives regarding the birth and psychology of sagging pants are wrapped in notions of people being controlled/dominated and/or lacking self-respect, but history shows society’s fashion outcasts are often people exhibiting strength through social and political defiance.  For example, dashikis and afros were seen as signs of defiance and militancy in the 1970s, as many Black Americans backlashed against American norms. Perhaps sagging pants came to popularity in the 1990’s, out of urban youth’s desire to defy social norms and expectations. Perhaps people began empowering themselves with sagging pants by blatantly rejecting the control of mainstream American society… A society that they felt would never fully grant them acceptance; so they stopped striving for the acceptance and worked to make it clear that there was no longer a care for mainstream approval… Perhaps.

For example, dashikis and afros were seen as signs of defiance and militancy in the 1970s, as many Black Americans backlashed against American norms. Perhaps sagging pants came to popularity in the 1990’s, out of urban youth’s desire to defy social norms and expectations. Perhaps people began empowering themselves with sagging pants by blatantly rejecting the control of mainstream American society… A society that they felt would never fully grant them acceptance; so they stopped striving for the acceptance and worked to make it clear that there was no longer a care for mainstream approval… Perhaps.

What do you believe led to the popular trend of sagging pants that emerged in the 90’s?