I want to develop the suggestion that cultural historians could take the Atlantic as one single, complex unit of analysis in their discussions of the modern world and use it to produce an explicitly transnational and intercultural perspective – Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic (1993)

Since publication, The Black Atlantic has left a major impression on scholars of African American Studies, cultural studies, southern studies, and countless transnational academic disciplines.

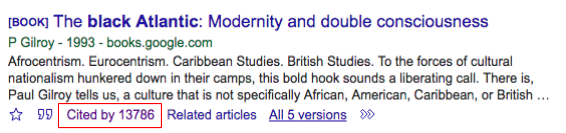

Especially in academic circles, it can be argued that the book has accomplished more than it set out to achieve in regards to inspiring cultural historians to take “the Atlantic as one single, complex unit of analysis,” as it has set people on the path to “use it to produce an explicitly transnational and intercultural perspective.” (15) In fact, many scholars and activists have cited The Black Atlantic in their explicit undertaking of transnational projects and intercultural perspectives that Gilroy outlines in the book. According to Google Scholar’s database, the book was cited over 1,200 times between 1993 and 2000. In the intervening years it has been cited over 13,700 times, at least at time of writing in April 2018.

Needless to say, it’s had (and continues to have) an impact on the academic community

But the question remains: what impact has the book that defined a region, a methodology, and a generation of scholars in the 1990s and early 2000s, had on interests around the world?

I offer a two-part answer here, but my conclusion is essentially that The Black Atlantic put the concept of hybridity on the map for Black Studies in a big way, which, despite being situated as a re-iteration of W.E.B Du Bois’s “double consciousness” within the older frame of “modernity,” advanced a new framework for black multi-consciousness or hybridity.

The Black Atlantic has definitely helped move scholarly interest from the national frame to the transnational frame.

While the line graph above shows that search interest (as measured by Google queries) in the term “transnationalism” and the topic “The Black Atlantic” have declined slightly since 2004—considering the current administration at time of writing, this is not surprising—it also shows that there is a relationship between the terms. As search interest has declined in “transnationalism,” so has search interest declined in “The Black Atlantic.”

This suggests that interest in Gilroy’s book, The Black Atlantic, is linked to interest in transnationalism, which should come as no surprise to those who’ve read The Black Atlantic. Its mission is intimately tied to the postcolonial theories and missions of scholars such as Homi K. Bhabha, who were living and writing what would eventually become the transnational turn in cultural studies of the 1990s.

Indeed, early in The Black Atlantic, we see Gilroy explaining and taking this turn away from a traditionally Anglophonic focus on national literatures:

Any satisfaction to be experienced from the recent spectacular growth of cultural studies as an academic project should not obscure its conspicuous problems with ethnocentrism and nationalism […] The question of whose cultures are being studied is therefore an important one, as is the issue of where the instruments which will make that study possible are going to come from. In these circumstances it is hard not to wonder how much of the recent international enthusiasm for cultural studies is generated by its profound associations with England and Englishness (5).

This quote is situated in a section that appears directly after Gilroy outlines the scope, problem, focus, subject, concepts, methods, intervention(s), and organization of The Black Atlantic (2-4). In discussing his organization at the end of this rundown, he writes “The final section [of the book] explores the specific counterculture to modernity produced by black intellectuals…It initiates a polemic which runs through the rest of the book against the ethnic absolutism that currently dominates black political culture” (5) This positions the book as a public address against (and undressing of) ethnic nationalism (among many, many other things).

Not long after the publication of The Black Atlantic, Gilroy brought this polemic to a mainstream audience when he went public on British television’s Channel 4 network and introduced D.W. Griffiths The Birth of a Nation (1915) as “a film which supports and affirms white supremacy” as well as “initiates a kind of taboo around intimacy between black and whites, which is still a living and central part of the Hollywood myth.”

Indeed, in this introduction to both film’s content as white supremacist propaganda, its form as a technolgical cinematic accomplishment, and its continuing legacy today, Gilroy recommends that cognitive dissonance is necessary in order to fully comprehend the film’s impact on the history of the United States and cinema. That is to say, the skepticism that Gilroy imparts to his televisual audience enacts The Black Atlantic‘s polemic against ethnic absolutism.

In a way this cognitive dissonance—or the ability to hold two opposing ideas in one’s mind at the same time—also enacts the concept of double consciousness that Gilroy uses to help frame The Black Atlantic, a concept which the book inevitably transcends with its discussion of black diaspora and the hybridity it introduced to black identity.

This brings us to The Black Atlantic‘s other main contribution.

The Black Atlantic helped redefine and resituate black identity as a hybrid identity that should be centered rather than an exclusively American, African, or African American identity formation that is marginalized.

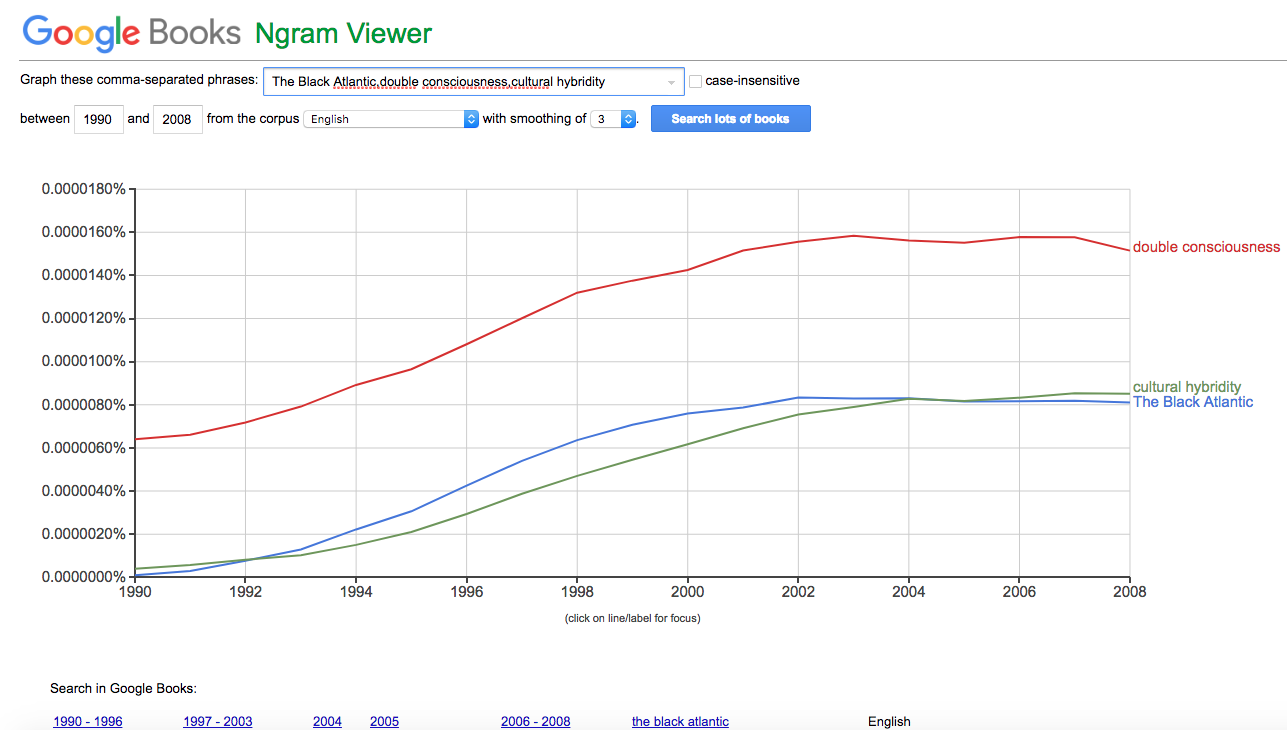

The word frequency graph above shows us that the words “The Black Atlantic,” “double consciousness” and “cultural hybridity” show a correlation in their appearance in books between the years of 1990 and 2008. Just looking at Gilroy’s title, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness, most people would not be surprised to see the relationship between word frequencies of “double consciousness” and “The Black Atlantic.” Unless they’re specialists, however, they might not expect to see that the words “cultural hybridity” appear on the proverbial map with around the same word frequency (and emerge at about the same time) as the words “The Black Atlantic.”

What this suggests is that while The Black Atlantic makes use of W.E.B Du Bois’s “double consciousness,” it’s true contribution to conversations revolving around Du Bois’s concept—the one for which it is most closely associate per Google Ngrams and in much of the scholarship that uses it—was advancing a new framework for “cultural hybridity,” or something more akin to black multi-consciousness (rather than double consciousness).

We can start to see why Gilroy advocates for a more culturally hybrid model of black identity for The Black Atlantic when he advocates for moving and re-centering the historical compass of modernity not in Western Europe, but in the Black Atlantic and its plantation slave economy. And this is arguably the largest crux of his book:

Plantation slavery was more than just a system of labor and a distinct mode of racial domination. Whether it encapsulates the inner essence of capitalism or was a vestigial, essentially precapitalist element in a dependent relationship to capitalism proper, it provided the foundations for a distinctive network of economic, social and political relations. Above all…it has retained a central place in the historical memories of the black Atlantic (55).

Here, we’re reminded of how Gilroy characterizes plantation slavery in Chapter 1: “capitalism with its clothes off” (15). This quote builds on that sentiment, but more importantly, it centers plantation slavery as the defining topos and locus of history and memory in the Black Atlantic world. Gilroy uses this argument to build a case for centering plantation slavery as the organizing principle that defined not only the the modern political and socioeconomic world, but the entire cultural framework upon which the concept of modernity was founded.

Staking this claim for the importance of a multiplicity of black perspectives, which emanate and spread from modernity’s cultural center rather than margin, Gilroy concludes, “The time has come for the primal history of modernity to be reconstructed from the slaves’ points of view” (55).

In all of these ways, and many more, The Black Atlantic brought hybridity to Black Studies and shaped the direction that the discipline would take towards a more enriched perspective on blackness that would be able to discuss multiplicities of black identity rather than simply doubleness.

Thinking to the Future

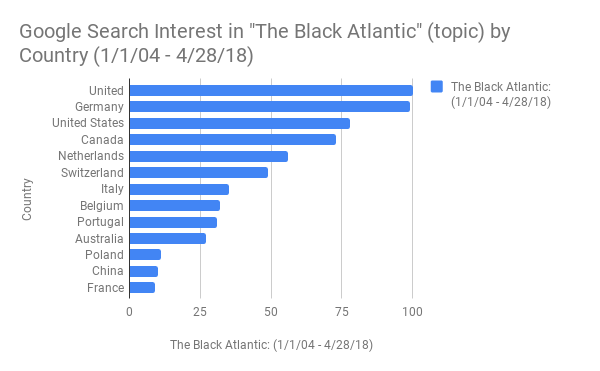

As the bar graph below illustrates, however, much work may remain to be done to bring The Black Atlantic‘s discussion of black hybridity to more global locations than Western Europe.

It is interesting that most of the nations where Google search interest is highest in The Black Atlantic are former colonist nations, whose populations are predominantly white. Should we be thinking about bringing Black Atlantic to more global audiences, such as Africa, in ways that don’t replicate colonial intellectual thought patterns? How might we do that?

— Joshua Ryan Jackson

Work Cited

Gilroy, Paul. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. Harvard UP, 1993.