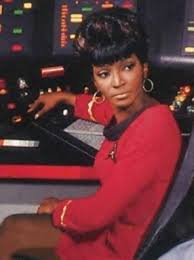

As Ytasha Womack points out in her book Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture, “it was an age-old joke that blacks in sci-fi movies from the ‘50s through the ’90s typically had a dour fate” (7). They were killed off: black hero, Ben (Duane Jones) in George A. Romero’s original The Night of the Living Dead (1968), is shot by the police at the end of the film. And white heroes trumped them: in Star Wars: Return of the Jedi (1983) Lando Carlrissian (Billy Dee Williams) looses the Millennium Falcon in a bet and, as an unfortunate result, Hans Solo (Harrison Ford) gets more screen time. Even in Star Trek: The Original Series (1966-69) — whose which creator, Gene Roddenberry, had openly articulated his investment in multiculturalism — Captain Kirk (William Shatner) repeatedly overshadows and even marginalizes Communications Officer Uhura (Nichelle Nichols), the only black character on the show (Kanzler). The prevalence of these tropes in other mainstream sci-fi series and films suggests that, in the words of Womack, “in the artistic renderings of the future by pop culture standards, people of color weren’t factors at all” (7). However, mainstream ‘90s sci-fi seemed to take Roddenberry’s vision much more seriously. In particular, black men were given more representation and occupied more positions of power in futuristic settings.

By 1999 Star Trek had been revived into three overlapping series that increasingly diversified. Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987-1994) still centered on a white hero, Jean-Luc Picard (Patrick Stewart), but it gave significant airtime to Lieutenant Commander La Forge (LeVar Burton of Roots and Reading Rainbow acclaim) and also introduced Worf (Michael Dorn),  the only Klingon in Starfleet (though, I admit, the racial implications of Klingons might be problematic). Star Trek: Deep Space Nine (1993-1999) showcased the series’ first black captain, Captain Benjamin Sisko

the only Klingon in Starfleet (though, I admit, the racial implications of Klingons might be problematic). Star Trek: Deep Space Nine (1993-1999) showcased the series’ first black captain, Captain Benjamin Sisko  (Avery Brooks) and Star Trek: Voyager (1995-2001), arguably the most diverse Starship crew, had a black Vulcan chief of security and tactical officer, Lieutenant Tuvok (Tim Russ who, they say, bears some resemblance to President Barack Obama).

(Avery Brooks) and Star Trek: Voyager (1995-2001), arguably the most diverse Starship crew, had a black Vulcan chief of security and tactical officer, Lieutenant Tuvok (Tim Russ who, they say, bears some resemblance to President Barack Obama).

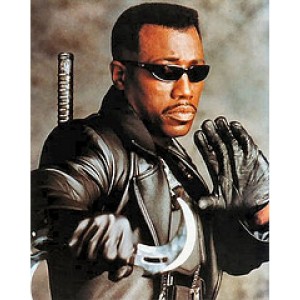

The mid 1990s transformed Will Smith from fun loving teen flirt in the family comedy series Fresh Prince of Bel-Air (1990-1996) into sci-fi action hero in the summer blockbuster Independence Day (1996) (making him one of highest grossing black celebrities in Hollywood). Smith followed Independence Day with two other sci-fi hits, Men in Black (1997) and Enemy of the State (1998). Around the same time, Wesley Snipes took to the big screen to play vampire superhero Blade (1998), and Lawrence Fishburne played the role of wise Morpheus in The Matrix (1999).[1]

Hyper masculinized black men were finally saving the world on sci-fi screens, instead of being killed-off or sidestepped. Yet there are important exceptions and integral supporting roles. Alfre Woodard played 21st century science and WWIII survivor, Lily Sloane, in Star Trek: First Contact (1996) and Gloria Foster played The Oracle in The Matrix. Vivica A. Fox played single mother, exotic dancer, and Will Smith’s love interest in Independence Day. Angela Basset won Best Actress at the Saturn Awards in 1995 for her role of Lornette “Mace” Mason in the film Strange Days (1995); Basset also played opposite Eddie Murphy in Vampire in Brooklyn (1995). Carol Christine Hilaria Pounder “CCH” played a freedom fighter Bertha Washington in Robocop 3 (1993) and FBI scientist, Dr. Hollis Miller, in Face/Off (1997).

There were also gender-bending black sci-fi characters. The most famous, perhaps, is Ruby Rod (Chris Tucker) in The Fifth Element (1997). Yet, Dwight Ewell’s performance of “Hooper X”, a black queer comic book artist who pretends to be both masculine and militant, in Kevin Smith’s Chasing Amy (1997) remains seminal.

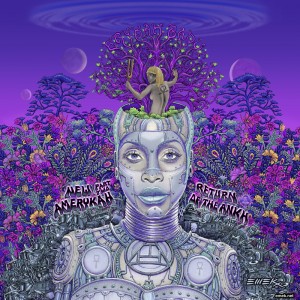

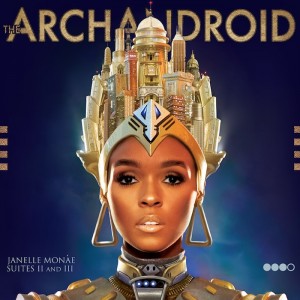

Strangely, the 2000s has brought rather conservative reboots of the original Star Trek series. Uhura, now played by Zoe Salada, is still a supporting character and plays a marginal role on the Enterprise. However, with the reemergence of Octavia Butler and the advent of recent Afrofuturism, developed by women like Ytasha Womack and Janelle Monae, the future looks black, and even feminist. —Rebecca Kumar

Footnotes and Works Cited

[1] originally written by black sci-fi screenwriter Sophia Stewart, who won a lawsuit against The Wachowski Brothers

Kanzler, Katja. Infinite Diversity in Infinite Combinations: The Multicultural Evolution of Star Trek. Universitatätsverlag Winter, 2004.

Womack, Ytasha L. Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi And Fantasy Culture. Chicago Lawrence Hill Books, 2013.