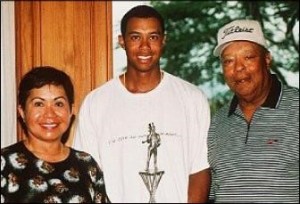

On April 13, 1997, 21-year-old Tiger Woods became the first person of African and Asian decent to win the golf Masters at Augusta National in Georgia. The win was a pivotal moment in history for African Americans. The race finally received well-deserved recognition in the sport. For years, African American golfers were overshadowed by other white competitors. Under the racist policy of America’s lynching, financial oppression, and other acts of hatred, Black men carried their golf game on. Some like Charlie Sifford and Lee Elder went on to stellar careers and became well known. But many others such as Teddy Rhodes, James Black, Bill Spiller, Nathaniel Starks, and Joe Roach never got that opportunity.

Not only did Tiger Woods win the Masters, but he also broke a record by scoring the lowest in the tournament’s history. Woods’s 72-hole score, an amazing 18-under-par 270, was the lowest in the tournament history and shattered a record of 271 shared by Jack Nicklaus and Raymond Floyd. After the win, African Americans were extremely proud of the athlete and his success in the sport; however, the celebration by fellow professional golfers was short lived. Long time PGA tour golfer Fuzzy Zoeller was asked on his feelings about Woods having such a record breaking tournament. Zoeller acknowledged Woods’ stellar tournament, calling his play “pretty impressive,” but quickly retorted, “The little boy is driving it well is doing everything it takes to win…tell him to enjoy it, and to not serve fried chicken next year…or collard greens, or whatever they serve.” Zoeller was referring to the Masters dinner, held each year on the Wednesday before the tournament. The year’s previous winner gets to decide the menu. Playing on tired and hateful stereotypes to make a cheap joke landed Zoeller in hot water. Woods ultimately forgave Zoeller, but it was obvious that golf (and the Masters Tournament) had deep issues with race. Even until the 1980’s one of Augusta National’s founders insisted that the caddies were only to be African American. It took an African American winner to for that ugly past and its enduring legacy to be confronted. It’s still being confronted, too. Sergio Garcia made a similar “fried chicken” comment regarding Tiger in 2012 (Nixon).

On April 24, 1997, a post-Masters interview between Tiger Woods and Oprah Winfrey aired and caused many African Americans to see their golf champion in a different light. During the interview, Winfrey asked Woods, “What do you call yourself?” Tiger answered: “Growing up, I came up with this name: I’m a Cablinasian.” Tiger Woods continued by explaining his multi-racial background saying how he is a mix of half Asian (Chinese and Thai), one-quarter African American, one-eighth Native American and one-eighth Dutch.

As stated previously, Tiger Woods’s claim of “Cablinasian” descent outraged many African Americans. Some even referred to him as a “sell-out.” Many would agree that the one-drop rule should be applied to Tiger’s situation, however, some have argued that Tiger Woods should not have to deny more than half his racial ethnicity to please black America. Woods was certainly aware of his ethnicity in 1997 and continued to be throughout his career and even today. He isn’t disowning Blackness by combining it with Asian and Caucasian. (Though it’s certainly worth an examination of the order of ethnicity in “Cablinasian”). An NAACP board member at the time, Julian Bond, countered the backlash of the Oprah Winfrey interview with saying, “As proud as I am of Tiger Woods, I realize I have to share him. He is part of a new reality. If people don’t feel comfortable with that, they are going to have to get comfortable with it”(Fletcher).

In light of the scandal that culminated in his divorce from his wife and a stint at a rehabilitation center, it’s worth reexamining Woods’ impact on golf. He hasn’t won a major since 2008, yet is considered one of the most popular golfers on the tour. His comments regarding race were met with angst from some white and black people, but has Woods’ enduring popularity and skill allowed him to transcend race? He certainly has the earnings to do so, earning hundreds of millions of dollars since his 1997 Masters win. He never has attempted to “cancel his blackness”; Woods could have let Sergio Garcia’s fried chicken comment slide, but instead, he addressed it by saying, “The comment that was made wasn’t silly,” and categorized it as “wrong, hurtful, and inappropriate” (Nixon). Woods never tried to downplay his blackness by fully addressing hate speech. If anything, Woods is trying to be more inclusive by representing the multiple ethnicity’s he identifies with. Perhaps that is why Woods continues to appeal to a diverse crowd of people.

—Jamari Devine, edited by Jeff Brown

http://www.aaregistry.org/historic_events/view/african-americans-and-golf-brief-history

http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/tiger-woods-wins-his-first-masters

Fletcher, Michael. “Tiger Woods Says He’s Not Just Black,” The Seattle Times. April 23, 1997. http://community.seattletimes.nwsource.com/archive/?date=19970423&slug=2535313

Nixon, Khari, “TIGER WOODS NEVER SAID HE WASN’T BLACK,” Mass Appeal, May 31, 2017. https://massappeal.com/tiger-woods-never-said-wasnt-black/.