Beta testing the Black 90s critical archive!

We welcome your feedback as we build a dynamic community.

← Navigate the decade via categories and tags.

[Connect] with us to contribute ideas.

Beta testing the Black 90s critical archive!

We welcome your feedback as we build a dynamic community.

← Navigate the decade via categories and tags.

[Connect] with us to contribute ideas.

Advertising campaigns had a great impact on Black American Communities and culture in the 1990s. Advertisements influenced 90’s politics, community health conditions, standards of beauty, technology, and countless other aspects of Black life. Holistically covering the impacts of such campaigns would likely require a novelistic thesis rather than a blog post. But in this writing, I will briefly cover some of the 90’s marketing/advertising campaigns that greatly impacted Black Americans. This is no attempt to capture everything, but rather a start; one that should be built upon over time.

Advertising campaigns had a great impact on Black American Communities and culture in the 1990s. Advertisements influenced 90’s politics, community health conditions, standards of beauty, technology, and countless other aspects of Black life. Holistically covering the impacts of such campaigns would likely require a novelistic thesis rather than a blog post. But in this writing, I will briefly cover some of the 90’s marketing/advertising campaigns that greatly impacted Black Americans. This is no attempt to capture everything, but rather a start; one that should be built upon over time.

George H.W. Bush’s “Revolving Door” advertisement was released in 1988 but had a large impact on the “tough on crime” initiatives that would drive many of the legal policies that increased levels of mass incarceration in the 1990’s [it’s almost needless to say that a disproportionate number of those legally affected were/are people with black and brown skin]. The ad attacked a prison weekend furlough program that had been supported by George H.W. Bush’s Democratic presidential challenger, Michael Dukakis, when Dukakis was governor of Massachusetts. The ad a focus was placed on a specific case/instance that terrified white America: The story of Willie Horton, a Massachusetts state prison inmate (and a dark-skinned African American male), who raped a woman while on a weekend furlough. The Ad successfully struck a major blow to Dukakis’ campaign, contributing to Bush winning 80 percent of the electoral vote. Bush successfully won his campaign, while also intensifying American race relations in a way that came with grave consequences for American minorities.

2. Nami Campbell and Gianni Versace

According to surveys conducted in the 1990’s, African-Americans were included in roughly 11 percent of all advertisements. However, Black People were most often depicted in minor, degrading, or background roles rather than prominent major roles. In 1991 Nami Campbell began making advertisements for Gianni Versace. This was revolutionary at the time because her representation pushed against notions that Black women didn’t have the ability to front international fashion brands… well, at least depending on one’s perspective. Though she was a dark-skinned Black woman, Nami Campbell still upheld other White/European standards of beauty: such as wearing synthetic long silky hair. One could argue that even in the midst of modeling with dark skin, she still perpetuated long-standing biased notions of beauty.

3) Mcdonalds Focused Heavily on Black Communities

During the 1990’s McDonalds targeted Black communities very heavily. One of the most memorable Advertising campaigns run by McDonalds in 1990 and 1992 have come to be known as the “Calvin’s got a job” ads. In the ads McDonalds used the story of and African American character named Calvin to display the social mobility potential of working at McDonalds. The ads even went as far as to imply that Calvin may become the owner of the restaurant one day if he kept working hard. Such campaigning focused towards Black communities positioned McDonald to look like assets in Black communities, rather than liabilities that were contributing to problems and capitalizing on their struggles. Zak Cheney-Rice from Mic.com wrote that “Mickey D’s efforts to highlight investment in the black community seem starkly in opposition to the rate at which they flood these same communities with extremely unhealthy food. This inevitably contributes to a slew of health issues, from heart disease in adults to ‘skyrocketing’ diabetes rates in children.”

4) Brown Tobacco and Brown Hands

“We don’t smoke that s_ _ _. We just sell it. We reserve the right to smoke for the young, the poor, the black and stupid.” ―R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company Executive (1992).

According to Connolly, G.N.’s essay “Sweeet and Spicy Flavours: Brands for Minorities and Youth”, during the period of 1995-1999, tobacco companies sponsored at least 2,733 programs, events, and organizations throughout the U.S, equaling a bare minimum of $365.4 million spent on such sponsorships alone. Many of the sponsorships consisted of small community-based organizations in Black and Minority Neighborhoods. Furthermore, studies from 1990-1998 found that there were 2.6 times as many tobacco advertisements per person in areas with an African American majority compared to white-majority areas. During this period, menthol cigarettes became a staple in Black American culture, becoming the cultural preference.

Let us know what Advertisement/marketing campaigns come to your mind when you think about the 90’s (comment below).

bell hooks is a feminist author and activist from the United States. Her name by birth is Gloria Jean Watkins, but she took the name bell hooks in honor of her maternal great-grandmother. hooks was born, one of seven children, to Veodis Watkins, a custodian, and Rosa Bell Watkins, a homemaker. She was raised in Hopkinsville, a segregated town in rural Kentucky, where she experienced firsthand both the hardships of segregated schools and, later, the process of integration.

Upon graduating high school, hooks attended Stanford University graduating with a BA in English in 1973 then continued on University of Madison, receiving her MA in English in 1976. Afterward, she split her focus between teaching Ethnic Studies at the University of South California and writing—publishing her first work, “And There We Wept,” a chapbook of poetry in 1978 and Ain’t I a Woman?: Black Women and Feminism in 1981—while, also, working towards a doctorate in literature at the University of California, which she achieved in 1983[1].

hooks spent her academic career as a scholar of African-American literature, writing her PhD dissertation on Toni Morrison, but her influences include a wide array thinkers including, amongst others: playwright Lorraine Hansberry, pedagogical theorist Paulo Freire, theologian Gustavo Gutiérrez, psychologist Erich Fromm, historian Walter Rodney as well as peace activist Thich Nhat Hahn and civil rights leaders, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.[2].

As such, hooks quickly became one of the foremost theorists of intersectionality, a framework which has recently gained great popularity in the analysis of systems of power within society and has combined her analysis of power relations with her academic career, writing texts dedicated to the topic of pedagogy. In her 1994 book Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom, hooks advocates for “a way of teaching in which anyone can learn.” One in which educators help students “transgress” boundaries of race, class, and sexuality to achieve intellectual and, so too, personal, social, and cultural freedom[3].

Implementing her own theories into practice, hooks, as a professor teaching at a variety of institutions from University of California, Santa Cruz and San Francisco State, to Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut and Oberlin College in Ohio, often found herself referencing pop culture in efforts to help students connect to theories of intersectionality. In doing so, she found herself grappling with new material in an entirely different field, media studies that would become the basis for her 1994 book Outlaw Culture.

In bell hooks’ own words: “Whether we’re talking about race or gender or class, popular culture is where the pedagogy is, it’s where the learning is. So I think that partially people like me who started off doing feminist theory or more traditional literary criticism or what have you begin to write about popular culture, largely because of the impact it was having as the primary pedagogical medium for masses of people globally who want to, in some way, understand the politics of difference. I mean it’s been really exciting for someone like me, both in terms of the personal desires I have to remain bonded with the working-class culture and experience that I came from as well as the sort of southern black aspect of that and at the same time to be a part of a diasporic world culture of ideas and to see how there can be a kind of interplay between all of those different forces. Popular culture is one of the sites where there can be an interplay[4].”

—Cecily McMillan

Works Cited

[1] Notable Biographies – bell hooks

[2] Notes on IAPL 2001 Keynote Speaker, bell hooks

[3] Teaching to transgress: education as the practice of freedom by bell hooks

[4] bell hooks – cultural criticism and transformation

Rabble-rouser, hero, thug, public servant, crackhead, role model, negro militant, freedom rider, scoundrel, prophet, radical, drug addict, philanderer, genius, convict, legend… he’s been called it all. When it comes to Marion Barry, the truth really is stranger than fiction and, like most things, it depends on your vantage point, it differs according to where you stand and, especially, which side of the tracks you live on.

Straight from the experts, the indisputable facts are as follows:

1) Marion Barry was a powerful black leader:

“In 1965, Marion Barry arrived in Washington to direct activities for SNCC […] a civil rights organization known for demonstrations, sit-ins, and boycotts. Mr. Barry was its first national chairman. In 1966, he led a one-day bus ‘mancott’ to protest a fare increase requested by D.C. Transit.

He organized a ‘Free D.C. Movement’ to press for home rule. He called D.C. police ‘an occupation army.’ [In 1967,] With financial support from the U.S. Department of Labor, he organized and directed a group known as Pride Inc., which put more than 1,000 inner-city youths to work From 1972 until 1974, Mr. Barry was the school board’s president. In 1974, he was elected to an at-large seat on the D.C. Council […where] he was instrumental in defeating a 1 percent gross-receipts tax on all city businesses, winning the gratitude of the business community. He helped get a pay raise for the police department. He was among early supporters of equal rights for gay men and lesbians.

As mayor of the District, Mr. Barry became a national symbol of self-governance for urban blacks. […] His programs helped provide summer jobs for youths, home-buying assistance for working-class residents and food for senior citizens. And he placed African Americans in thousands of middle- and upper-level management positions in the city government that in previous generations had been reserved for whites[1].”

2) The FBI pursued Barry for the better part of the 1980’s:

“For eight years, FBI agents were trying to get Barry to a point where they could read him his rights. They went through his bank records, tax returns, American Express bills, and they staked out his home. No luck. They even set up a fake consulting firm to try to infiltrate the mayor’s inner domain.

[…] Then, as part of this ‘scrupulously fair’ operation, the pursuit team decided to find a woman whom Barry trusted. ‘We talked about how the easiest way to get Barry was with a woman,’ a high-level law enforcement officer told The Post. Rasheeda Moore, then in California, fit the bill. Her fateful invitation to Barry to meet her at the Vista International Hotel followed.

With Moore – ‘the cooperating witness,’ in FBI lingo — was an FBI undercover agent who allegedly brought Barry the crack cocaine he allegedly asked and paid for. All this was recorded by cameras and audio machines in the bathroom and the joining bedroom[2].”

Shortly before 8:30 PM on January 18, 1990, Mayor Barry arrested at the Vista Hotel by FBI and D.C. police, the result of a sting operation coordinated jointly by the United States Attorney’s Office. In short order, Barry was charged with misdemeanor drug possession of crack-cocaine and released to face the facts of that evening, under the scrutiny of a nation divided, in the cold, hard light of day[3].

When the story broke the next day, it sparked, yet another, sharp divide in what was already a racially charged city. The overwhelming majority of black folks rallied around the mayor, accusing the white—mostly, wealthy Republican—officials of targeting Barry as a powerful leader who had effectively created an economy for and constituency out of, what was before Barry’s tenure, a wholly disenfranchised black community. Put simply by Jonetta Rose-Barras, award-winning journalist and author of The Last of the Black Emperors: The Hollow Comeback of Marion Barry in the New Age of Black Leaders (Bancroft Press 1998), “Black people thought, ‘He was set up[3]!’”

In the days and weeks leading up to his trial, crowds of black folks sprang up all over the city, waving signs that read “MAYOR BARRY MAY NOT BE PERFECT, BUT HE IS PERFECT FOR US”, “We thought lynching was outlawed in the 1920’s”, ‘Stop the persecution of our black leaders!” and the like, while community leaders made fiery speeches erupting in thunderous applause and endless cheers of “Barry! Barry! Barry!” One such preacher seemed to embody the spirit of general disillusionment and widespread anger at the personal nature of the attack on their mayor when he concluded his oratory with a bleak pronouncement and the wave of a condemnatory finger: “There is no justice in America for the black man or black woman. Let us not deceive ourselves[3].”

White voters, on the other hand, almost unilaterally called for his immediate impeachment, posting signs all over the city to that effect. As for their take on race at play in Barry’s case, consider the exchange between one every-day, middle-aged white lady and morning show host, Cliff Kincaid of WNTR, the flagship radio station for televangelist Pat Robertson’s conservative talk network. Calling in the woman exclaimed, “If I hear one more black claim that it’s because he’s black, I’m going to throw up!” Commiserating, Kincaid chimed in, “And let’s dismiss all this nonsense about entrapment. Nobody forced him to go to that hotel. Marion Barry is a pathological liar. He’s a crack head[3].”

In the trial that began on June 20, 1990, the U.S. Attorney ultimately brought 14 charges against Marion Barry: three felony counts of perjury, 10 counts of drug possession, and one misdemeanor count of conspiracy to possess cocaine from the night of his arrest[4]. The criminal trial ended in August 1990 with a conviction for only one possession incident, which had occurred in November 1989, and an acquittal on the other one. “I believe [the government was] out to get Marion Barry,” one juror said. U.S. District Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson declared a mistrial on the 12 deadlocked charges[5]. The mayor was sentenced to six months in prison but came back to win a council seat in 1992 then rose, again, to claim the office of the mayor in 1994, where he remained for two terms[6].

FOR A COMPREHENSIVE TIMELINE OF MARION BARRY’S LIFE, CLICK HERE!

—Cecily McMillan

Works Cited

[1] Washington Post Obituary

[2] Of Course it Was Entrapment – Washington Post

[3] The Nine Lives of Marion Barry

[4] Charges and Verdicts in Barry’s Trial

[5] Chasm Divided Jurors in Barry Drug Trial

[6] Marion Barry: Making of a Mayor

You should never argue about religion, politics, and…umm… sagging pants. The 1990’s gave rise to many fashion trends, but sagging pants has stood as one of the most controversial. People have argued over the historical roots, the psychology behind people showing their behind (slight word-play pun intended), and there have even been instances of people pushing to ban sagging pants altogether. “Which movie was better: Friday or Boyz n the Hood?”, “Who had a bigger impact: Biggie or 2pac?”, “Did O.J. really do it?”, and “Why did many people in urban areas begin sagging their pants?” are all topics that universal scholars and barbershop clients could endlessly debate.

You should never argue about religion, politics, and…umm… sagging pants. The 1990’s gave rise to many fashion trends, but sagging pants has stood as one of the most controversial. People have argued over the historical roots, the psychology behind people showing their behind (slight word-play pun intended), and there have even been instances of people pushing to ban sagging pants altogether. “Which movie was better: Friday or Boyz n the Hood?”, “Who had a bigger impact: Biggie or 2pac?”, “Did O.J. really do it?”, and “Why did many people in urban areas begin sagging their pants?” are all topics that universal scholars and barbershop clients could endlessly debate.

One popular narrative regarding the rise of sagging pants in the 90’s is that prison fashion trickled over to everyday fashion worn in the street(s).This argument has grounds because between the years 1990-2000, U.S. prison rates grew from roughly 800,000 to 1,400,000. Prison populations aren’t allowed to wear belts and are often provided with oversized clothes. Many believe that such prison clothing distribution practices led to a normalization of sagging pants; one that ex-prisoners did not abandon upon being released back into their personal communities. Furthermore, about a decade before the 90’s, various influential sources, such as the Washington Post, began publishing articles declaring that “Prison Has Become ‘Rite of Passage’”. If such a theory is true, then it may strengthen the arguments of those who believe that sagging pants originated in prison; if prison is a rite of passage (for at least some groups or individuals), then quite naturally various people would lean towards dressing as if they’ve been imprisoned.

There’s also a separate prison origin-based belief, that accredits the initial act of prisoners sagging their pants to sexuality, rather than a sheer lack of belts and better clothing. A commonly perpetuated idea has been that prisoners began showing their behind in order to advertise sexual availability. It has also been said that certain prisoners were forced to wear their pants below the waist in order to communicate to other prisoners that they were taken (“taken” as in concurred/controlled by another inmate). Though such narratives are popular, like the Big Bang theory, their accuracy has yet to be completely confirmed.

Stepping away from the prison narrative, some argue that the trend of sagging pants that rose in the 1990’s was simply a result of young people in urban communities trying to maneuver poverty: children and teenagers tend to have many growth-spurts, and in the midst of economic struggles, continuously buying clothes for growing children can quickly become costly. A solution implemented by many parents and young shoppers was to buy clothes that were too big, so that the intended wearer would have an opportunity to grow into them over time (a practice that is still very common). due to many families struggle in urban communities, purchasing belts were sometimes viewed as a luxury, rather than a necessity. Some people believe that the two factors (oversized clothing and not being able to afford belts) led to the trend of urban youth unapologetically wearing baggy pants that hung below their waistline.

Though as human beings we tend to search for simple explanations, the reality is that few things are black and white, and it’s possible that all the arguments/narratives above may hold some level truth. But to shake up the conversation a bit, if the saying “there’s nothing new under the sun” holds any validity, then potentially the most accurate answer regarding the roots and psychology behind the birth of sagging pants in the 90’s can be discovered through exploring eras prior to the decade.

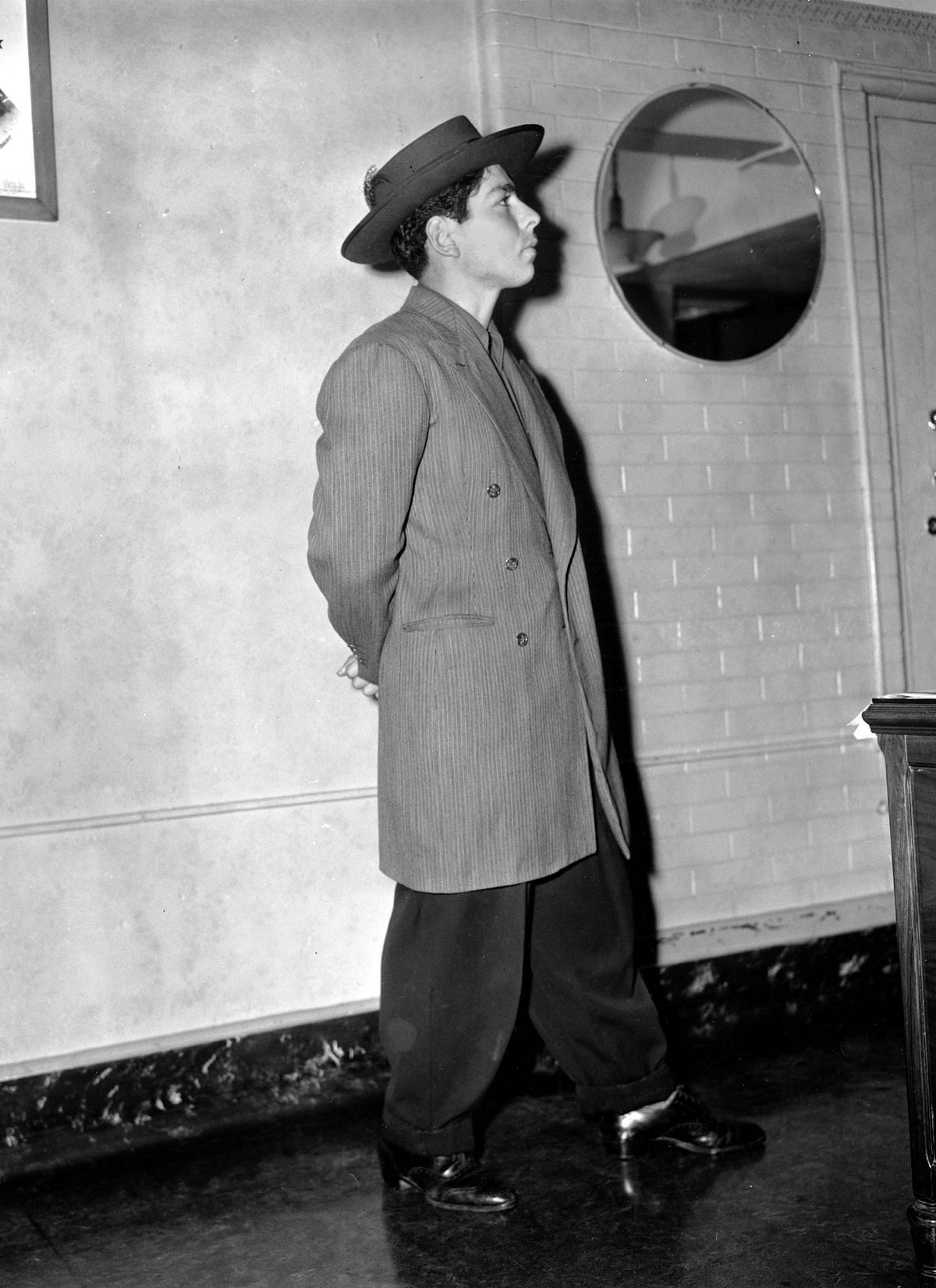

Historian Luis Alvarez states that zoot suits of the 1930s and 1940 “share much of the same DNA as the trend of sagging pants that gained popularity in the 1990’s. Zoot suits were baggy, worn by youth in urban spaces and associated with criminal activity by Black and Latino people.” The suits were initially worn in such a way due to people not being able to afford fitted suits and was eventually adopted as an intentional style linked to Jazz music. Sagging pants started out being worn by youth in urban spaces and was/is associated with criminal activity by Black and Latino people. Also, the affordability and mainstream music adoption aspect has perpetuated the popularity of the style as well. One important thing to note about the zoot suit wearers is that, for them, the style represented a form of moral and political defiance. Luis Alvarez states that zoot suits were “ways that people made statements about their relationships to other people and their circumstances”. A majority of narratives regarding the birth and psychology of sagging pants are wrapped in notions of people being controlled/dominated and/or lacking self-respect, but history shows society’s fashion outcasts are often people exhibiting strength through social and political defiance.  For example, dashikis and afros were seen as signs of defiance and militancy in the 1970s, as many Black Americans backlashed against American norms. Perhaps sagging pants came to popularity in the 1990’s, out of urban youth’s desire to defy social norms and expectations. Perhaps people began empowering themselves with sagging pants by blatantly rejecting the control of mainstream American society… A society that they felt would never fully grant them acceptance; so they stopped striving for the acceptance and worked to make it clear that there was no longer a care for mainstream approval… Perhaps.

For example, dashikis and afros were seen as signs of defiance and militancy in the 1970s, as many Black Americans backlashed against American norms. Perhaps sagging pants came to popularity in the 1990’s, out of urban youth’s desire to defy social norms and expectations. Perhaps people began empowering themselves with sagging pants by blatantly rejecting the control of mainstream American society… A society that they felt would never fully grant them acceptance; so they stopped striving for the acceptance and worked to make it clear that there was no longer a care for mainstream approval… Perhaps.

What do you believe led to the popular trend of sagging pants that emerged in the 90’s?

Background, God’s Property:

God’s Property, founded in 1992 in Dallas, Texas, was developed by Linda Ray Hall-Searight, a public-school music teacher, and her son, Robert Sput Searight, who has since gone on to become a world-class drummer and Grammy Award Winner. The original ensemble included more than fifty singers and a band of approximately twenty musicians, recruited mostly from Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing and Visual Arts High School (where other notable alumni such as Erykah Badu, Willie Hutch, and Roy Anthony Hargrove also attended[1].)

In 1993 the choir collaborated with Kirt Franklin, providing backup vocals for his 1995 album Whatcha Lookin’ 4. In turn, Franklin appeared on and helped produce the group’s debut album, God’s Property from Kirk Franklin’s Nu Nation, released May 27, 1997. The album won the NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Gospel Artist, the NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Music Video, the Soul Train Music Award for Best Gospel Album, and the Grammy Award for Best Gospel Choir or Chorus Album in 1998. The album was #1 on the R&B Albums chart for 5 weeks, #3 on Pop Charts, and would go on to be certified triple platinum with over 3 million copies sold across the United States[2]. The lead single “Stomp”, featuring Cheryl “Salt” James (of Salt-N-Pepa), made it onto Hot 100 Airplay, Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Airplay, Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Recurrent Airplay, Rhythmic Top 40, The Billboard Hot 100, and Top 40 Mainstream[3].

Interview with L. Nyrobi N. Moss:

CECILY: Hello, this is Cecily McMillan of writing for Professor Scott Heath’s course: Archiving the Black 90’s. I am attempting a new way at archiving the black nineties by speaking to a Ms. L. Nyrobi N. Moss, who was a foundational and central member to the musical group, the musical phenomena: God’s property, that pretty much developed the genre of Urban Contemporary Gospel. In which way did you find a path to participate in the arts and the music of the nineties?

NYROBI: So, I went to performing arts high school, I also went to performing arts junior high school as well, but my interest in the entertainment industry came via arts magnet, which was a breeding ground for a lot of major artists, but a lot of creative expression in Dallas and, essentially, spreading to the world. So, in addition to attending arts magnet, I also was one of the original founding members of the choir called God’s Property Ensemble and God’s Property was of course released under Kirk Franklin’s label in 1997. However, before that release, we already had a really huge following in the Dallas, Houston, L.A., and a lot of different markets as far as Gospel groups were concerned, and that also kind of led us to work with other artists and playing with different background vocals and singing on other people’s tracks. But we were also signed by B-Rite, a division of Interscope, so Tupac Shakur was one of my label mates. So that is my introduction to the nineties in music.

CECILY: You said that album popped off, like, the group was signed by the label in ’97?

NYROBI: No, we were assigned before 97. The album got released in 97. So, the first full album was God’s Property with Kirk Franklin’s The Nu Nation. However, I want to note that we were God’s Property before Kirk Franklin was Kirk Franklin, and I know because I sang on his first album. But, either way, you know, it was the terminology of who gets picked up first in the industry versus who releases whom. So, at the time he had the platform and he did a lot of producing on our first album when we worked with him.

CECILY: OK. So, 1997. You’re in high school?

NYROBI: No, I was way out of high school. But God’s Property started when I was [at Booker T. Washington] high school. We first formed God’s property, I want to say in ’93-’94.

CECILY: Booker T. Washington, was it a racially diverse high school?

NYROBI: Booker T. Washington for the Performing and Visual Arts was racially diverse. It was culturally diverse, religiously diverse. Some of my best friends were, you know, satanists and had shaved heads, and we all were just these artists that lacked on things, but we didn’t have a problem just crossing over and figuring out who was what. You know, at Booker T. you could see all these different genres in silos and nobody really was kind of singled out. It was just like, you got your group of those who are visual artists and those are the vocals. And those were the hip-hop kids and, so, the music tied us all together.

CECILY: So, I’m thinking about the form of music that you’re talking about. And obviously there are songs, especially in the nineties, I mean the first one that comes to mind for me obviously as Madonna, Like a Prayer. But the incorporation of Gospel into songs, especially ballads, is a super powerful mechanism. Did that become popular in the ’90s?

NYROBI: I want to be clear: It wasn’t about incorporating Gospel. Gospel is pretty much the root. If you find any artist, especially black artists, they’re going to tell you their group got started in Gospel. The reason why God’s Property was so pivotal was because we were young, and we were fun and we were hip and we used to bring, you know, rap melodies [into the music]. Like when I was in junior high school, I played classical piano and I hated every minute of it, which is why I switched over to theater, musical theater, because it was boring. So, God’s Property was the first time that I knew that music could be fun and that it could be interesting, and it could have a great high energy. And Gospel, in turn, like we used to bring down houses and churches. Our biggest criticism was the fact that, you know, that we were singing devil songs and we were jamming to Gospel music. And we were doing that in church, and we brought such high energy to it, and, you know, we were too radical. So, people couldn’t tell the difference between what our music was and what Gospel was and that was a problem. Now it’s old hat. Now, you can find you all these different Gospel artists and they all hip-hop, and this and that and the third. But that wasn’t done then, you know. We used to get a lot of flack for that.

CECILY: Yeah, I could see that on the church side. But also, thinking about myself as a teenager, it seems totally incomprehensible that I would get together with a group of my friends and want to do something Gospel inspired. So, I’m clearly missing a link here. How did this emerge?

NYROBI: They’re all linked. The interesting thing is that R&B, hip-hop, they all have roots in Gospel. If you ask any artist where they came up, where they got their musical influences, then they’re gonna say in the church. So, the thing about that is that church, especially in the black community, always influences where we are socially, where we are politically, you know, how we build movements, what that looks like. So, I will say that it wasn’t far removed from us because we used to be in a church doing jam sessions. And even jazz, which is one of the greatest art forms ever because it has these different musicians that’s riffing, that’s doing all this other kind of improvisational stuff. All those things were not removed from us. They were all part of who you were. And so, therefore, we were young. We lived, we loved, we lived hip-hop. We lived where hip-hop started, what it was all about, know what I’m saying? In the nineties, we had your 2 Live Crews and different artists… when hip-hop was kind of risqué. But where we were and where we sat was in this place where it was all creation, it was all music for us. We blended all this together and they weren’t separate for us.

Works Cited

[1] Wikipedia – Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing and Visual Arts

In 2015, Interning for one of South Florida’s most influential record labels, I was given opportunities to communicate and interact directly with the label’s founder and CEO on a regular basis. Like a curious child asking their parents millions of questions in an attempt to gain some understanding of this complicated world we live in, I took advantage of every opportunity to ask the CEO questions that I felt could possibly help me gain a deeper understanding of the music industry. One day after drenching the CEO with a rainstorm of questions, he told me that he has always aimed to be like Master P: Master P greatly influenced the way he ran his label and the various ways that he chose to maneuver the music industry. Most notably, Master P influenced him to push for “80/20” distribution deals, and to maintain ownership of all master recordings produced by his label.

In 2015, Interning for one of South Florida’s most influential record labels, I was given opportunities to communicate and interact directly with the label’s founder and CEO on a regular basis. Like a curious child asking their parents millions of questions in an attempt to gain some understanding of this complicated world we live in, I took advantage of every opportunity to ask the CEO questions that I felt could possibly help me gain a deeper understanding of the music industry. One day after drenching the CEO with a rainstorm of questions, he told me that he has always aimed to be like Master P: Master P greatly influenced the way he ran his label and the various ways that he chose to maneuver the music industry. Most notably, Master P influenced him to push for “80/20” distribution deals, and to maintain ownership of all master recordings produced by his label.

“Master P was a real n*gga, that put his arms around me and showed me the business…I knew the creative side, but he showed business… If it wasn’t for No Limit, it wouldn’t be no money in rap… It was NO MONEY in rap until Master P came out!” —Snoop Dogg

Essentially Master P (MP) and No Limit Records laid a foundation in the mid to late 1990’s that forever impacted the music/entertainment industry. Far before becoming a household name, or even fully being able to sustain himself financially, Master P was already set on conducting business in the music industry on his own terms. As an unsigned artist struggling early in his career, Master P made a pivotal decision to turn down a million-dollar record deal presented to him by Interscope Record’s Jimmy Iovine. Unlike the average unsigned artist at the time, who would have likely quickly jumped at such an offer without hesitation, Master P realized that he possessed the ability to make that same amount of money, and far greater amounts, without committing to a major label. He declined the offer and went on to build a legacy of independence, innovation, and business savvy execution.

The year of the Jimmy Iovine’s offer hasn’t been specified, though it is estimated that the deal was proposed in late 1994 or 1995. Master P turned DOWN the deal and turned UP his grind with no brakes; By 1996, Master P and his independent record company, No Limit, had established a strong growing fanbase of supporters in multiple cities throughout the southern region and west coast. Gearing up to release his fifth studio album, Ice man, he made the decision to expand on a major level. But unlike other Hip-Hop artists and independent labels at the time (and prior), Master P used his business savvy ways to achieve mainstream success while maintaining artistic and company independence…

In 1996, Master P noticed that a bulk of rap artists and small labels were committing to record deals that only allowed them the receive about 10% of all profits from their work. But Master P refused to submit himself or his company to such economic exploitation. He turned the tables on the industry and set a blueprint for other artists and independent labels to follow for generations to come: He did research and found out that (at the time) Michael Jackson (MJ) had the best deal in the music industry. From there, he reached out to Michael Jackson’s lawyer for assistance. MJ had a record deal with a major label; Master P solely wanted a distribution deal that held similar elements―Most notably an 80/20 profit split, with No Limit records receiving the split’s larger portion. Michael Jackson’s Lawyer charged MP $25,000 to help him obtain an 80/20 distribution deal with Priority Records. [Many sources state that the deal was “80/20”, but in various interviews Master P has mentioned that is was “85/15”.] Whether “80/20” or “85/15”, one thing is for certain: Master P convinced Priority records to commit to a deal where No Limit records would maintain ownership of all recording masters, as well as receive the bulk of any profits. Priority records agreed to handle distribution, while No Limit records was expected to take care of all marketing and promotion costs. At the time of the deal, Priority Records didn’t expect Master P and No Limit to gain many sells. But to their surprise, Master P’s 1996 album “Ice Cream Man” eventually became certified Gold (selling over 500,000 copies).

“Ice Cream Man’s was the tip of the iceberg; the beginning of a No Limit dynasty… one that literally lived up to its name. Throughout the years 1996-2000, Master P and No Limit records produced many successful artists, released multiple platinum and gold albums, put out many independent films, and even had a professional wrestling stable with World Championship Wrestling at one point. MP literally did nearly everything that one can think of; some of Master P’s further business ventures outside of entertainment consisted of clothing lines, jewelry lines, gas stations, fast food franchises, energy drinks, phone sex companies, toy making, and much more. Throughout all of his investments and ventures in the 90’s, Master P maintained an independent status within the music/entertainment industry. He was one of the first figures in Hip-Hop (and potentially music in general) to achieve high levels of mainstream success without succumbing to traditional recording contracts. His success in 90’s showed Hip-Hop moguls and artists that it was/is possible for them to conduct business on their own terms and that they do not have to be exploited by major record companies.

O.J. Simpson

On October 3, 1995 Orenthal James Simpson (O.J.) was found “not guilty” of the murders of Nicole Brown and Ron Goldman after only four hours of deliberation. The response from the American people was split. Many white audiences stared in shock and disbelief while black audiences cheered and celebrated the verdict. What was a huge miscarriage of justice to white people felt like vindication and validation to black people. It proved that the LAPD was corrupt and racist towards Black people. But Simpson’s acquittal only benefitted Simpson and did nothing for relations between the Black community and the  LAPD, a community Simpson had erased from his life in pursuit of fame, fortune, and celebrity.

LAPD, a community Simpson had erased from his life in pursuit of fame, fortune, and celebrity.

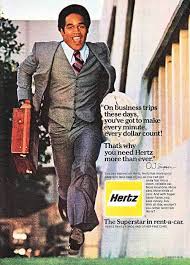

Before Simpson stepped into the spotlight for the murders of Brown and Goldman, he was already a household name. Simpson first found fame as a college running back at the University of Southern California.[1] An NCAA record  breaker and a Heisman Trophy winner, Simpson shined as the darling of USC football. He later went on to play professional football with the Buffalo Bills and the San Francisco 49ers, breaking records along the way. During his time in professional football, Simpson became the spokesman for Hertz, the rental car service, and Chevrolet which bolstered his rise to fame. Simpson retired from football in 1979 to pursue other career options.

breaker and a Heisman Trophy winner, Simpson shined as the darling of USC football. He later went on to play professional football with the Buffalo Bills and the San Francisco 49ers, breaking records along the way. During his time in professional football, Simpson became the spokesman for Hertz, the rental car service, and Chevrolet which bolstered his rise to fame. Simpson retired from football in 1979 to pursue other career options.

Simpson’s time in the national spotlight came during the Civil Rights Movement. However, Simpson made sure to stay far from racial conflict. Simpson not only declined to take a stand, he claimed ignorance to the racial upheaval around him. In an interview, when a reporter asks Simpson about the 1968 Summer Olympics boycott, he had “no comment.”[2] Simpson endeavored to live his life colorless, erasing his blackness and just being allowed to live as a man. In Ezra Edelman’s documentary O.J.: Made in America, a friend comments that Simpson was “seduced by white society.” This erasure of color from Simpson’s life meant that he could be palatable to the white world he wanted to take part in. In a commercial for Hertz, Simpson was depicted running through the airport, surrounded by white people cheering him on.[2] Much of Simpson’s adult life mirrored this Hertz commercial. For many of the white people in Simpson’s life, he was one of the few black people they knew, and they were all rooting for him. Simpson had been completely immersed in the world of whiteness, leaving his blackness behind. So, how did Simpson come to symbolize the struggle of Black America during his murder trial?

he could be palatable to the white world he wanted to take part in. In a commercial for Hertz, Simpson was depicted running through the airport, surrounded by white people cheering him on.[2] Much of Simpson’s adult life mirrored this Hertz commercial. For many of the white people in Simpson’s life, he was one of the few black people they knew, and they were all rooting for him. Simpson had been completely immersed in the world of whiteness, leaving his blackness behind. So, how did Simpson come to symbolize the struggle of Black America during his murder trial?

Two years before the murders and Simpson’s trial captured national attention, the eyes of the world were rivetted on Los Angeles awaiting the verdict of the LAPD cops responsible for the Rodney King beating. King’s beating was caught on camera and the cry for justice could not be ignored. The abuse the LAPD heaped on the Black community had been documented and reported for decades and had gone unanswered. Many believed that though the King beating was unfortunate because it was recorded and shared with the world, there would finally be justice for a community terrorized by the LAPD. The resulting ‘not guilty’ verdict shocked and angered many. The Black community raged at the blatant miscarriage of justice and took to the streets spawning riots that would last four days. The violence was not a response to just the King verdict; it had been brewing for decades. The L.A. riot may have been cathartic, but it was not justice. The LAPD and racial inequality still won.

Though Simpson had abandoned the black community, for many represented the height of success for a black man. Simpson’s football prowess rocketed him to the wealth and power black men rarely see, especially a black man coming up from poverty and government housing. Simpson may have tried to erase his blackness, but for black people he was a role model and something to reach for. Even black people understood that Simpson’s acceptance by a white audience was responsible for his status. Simpson had made it despite being a black man in white America. When Simpson was arrested for the murders of Brown and Goldman, much of black America was ready to root for him.

With the “Dream Team” consisting of Johnny Cochran, Robert Shapiro, F. Lee  Bailey and a few other high-powered attorneys at his side, the trial began in January 1995. Marcia Clark and Christopher Darden were the District Attorneys prosecuting the case and built a case on the evidence collected at the crime scene and Simpson’s estate. But it was not enough. The world watched as Cochran and the Dream Team presented a defense that alleged mishandling of evidence and mishandling of evidence by the prosecution’s star witness, Mark Fuhrman. A trial that should have been about the science quickly turned into one about race and the history injustice and racism by the LAPD against black people. Johnnie Cochran spent the next year reconstructing O.J.’s blackness and building him as a symbol of racial injustice. Even though Simpson had not concerned himself with being Black in America, Black people rallied around him when it appeared he was being railroaded by the LAPD. While race was not the only reason the prosecution lost its case, it was the most defining. In a poll by the L.A. Times, 65% of whites believed Simpson was guilty, but 77% of blacks believed he was innocent.[3] In an interview for Edelman’s documentary, juror Carrie Bess asserts that Simpson’s acquittal was payback for the Rodney King beating and acquittal, but another juror denies this instead saying the prosecution lost the case because it was weak. But maybe it was a bit of both.

Bailey and a few other high-powered attorneys at his side, the trial began in January 1995. Marcia Clark and Christopher Darden were the District Attorneys prosecuting the case and built a case on the evidence collected at the crime scene and Simpson’s estate. But it was not enough. The world watched as Cochran and the Dream Team presented a defense that alleged mishandling of evidence and mishandling of evidence by the prosecution’s star witness, Mark Fuhrman. A trial that should have been about the science quickly turned into one about race and the history injustice and racism by the LAPD against black people. Johnnie Cochran spent the next year reconstructing O.J.’s blackness and building him as a symbol of racial injustice. Even though Simpson had not concerned himself with being Black in America, Black people rallied around him when it appeared he was being railroaded by the LAPD. While race was not the only reason the prosecution lost its case, it was the most defining. In a poll by the L.A. Times, 65% of whites believed Simpson was guilty, but 77% of blacks believed he was innocent.[3] In an interview for Edelman’s documentary, juror Carrie Bess asserts that Simpson’s acquittal was payback for the Rodney King beating and acquittal, but another juror denies this instead saying the prosecution lost the case because it was weak. But maybe it was a bit of both.

–– A. Latson

[1]https://www.biography.com/people/oj-simpson-9484729

[2]Edelman, Ezra. O.J.: Made in America.

[3]Decker, Cathleen. “THE TIMES POLL: Most in County Disagree with Simpson Verdicts.” Los Angeles Times. 8 October 1995.

When W.E.B Du Bois wrote about the quintessential black experience in America he defined is as double consciousness, putting into words an identity that is divided into multiple facets. (Black and American)

He uses this idea of a “veil” to metaphorically describe 3 things: literal skin difference as a physical separation, white people’s lacks of clarity to see Blacks as true Americans, and black’s inability to see themselves outside of how white Americans see them.

“One ever feels his two-ness- an American, A Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one day body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

Double consciousness and the veil convey underlined issues of racism and the social constructs to which race builds prejudice in a black American vs. white American nation. But let us be honest: There is a second sensation of double consciousness black Americans are facing within the realm own their own black community. Colorism can be formally defined as prejudice or discrimination against individuals with a dark skin tone, typically amongst people of the same race. It is Colorism that gave birth to the light-skinned vs. dark-skinned beef.

Black 90s sitcoms showed us colorism in the following variations: “Aunt-Viv” Who?, Pam vs. Gina, and what I like to call revenge of colorism: The Hilary Banks, and Whitley Gilberts.

It is safe to say that colorism is a kin to racism that black folks have taken right in. Early twentieth century there was the Clark doll experiment in which children would answer questions regarding characteristic in which they attribute to a doll. Results showed children attributed traits like “prettiness, and good behavior” to lighter dolls, and “ugliness and badness” to darker dolls,” proving the social construct of race begins early, leaving much time for its ideologies to truly embed in one’s beliefs.

Well into the mid-twentieth century we had the paper bag test, in which black institutions would use a brown paper bag to determine whether an individual’s skin was light enough to gain membership.

Too, let’s acknowledge the existence of passing in which lighter-skinned blacks or multi-racial persons were able to assimilate into white culture to avoid the legal and social conventions that being black would subject them to.

Now here comes the 90s, administering deadly doses of colorism:

I think it’s safe to say the impacts of colorism is part of the reason why so many viewers weren’t here for Aunt Viv 2.0. For the first three years of “The Fresh Prince” we bonded so well with Janet Hubert’s loveable portrayal of Aunt Viv with her feisty, joke cracking personality, accompanied by her beautifully-fixed brown-chocolate skin.

Hubert lasted half way through the series until they brought Daphne Reid in. Aunt Viv 2.0 was much lighter, and noticeably less feisty. It appeared as if Aunt Viv 2.0 was the example of what it means to be seen and not heard, while the original dancing diva of Aunt Viv could have easily stolen the show. But there it is; a stereotype that appoints darker skinned women as more antagonistic, while Janet Hubert’s replacement with a light-skinned women supports the notion that the best “do over” for a feisty darker toned woman is a less antagonistic, light-skinned woman. Viewers yearned for Hubert’s return. They never got it.

The 90s also gave us aspiring news anchor Dexter Jackson, in Livin’ Large who finally got his chance on the local news only to end up with a mistaken image of himself (lighter toned and European features) in which was considered ideal. This is an example of the impact colorism can have on oneself.

Now let’s really talk: Pam and Gina. For five years viewers watched as Gina (played by Tisha Campbell) was the kind, beautiful, light-skinned, sought-after and perfectly silly partner of Martin. On the other hand there was Pam; (played by Tichina Arnold) dark-skinned, loud and confrontational, though still attractive. Gina was the love interest to the main face of the series, while Pam was simply Gina’s combative best friend. Pam’s relationship with Martin was playfully explosive, with the two consistently making fun of each other. Martin consistently referencing Pam’s “bad attitude,” “nasty mouth,” “buck-shots;” while also deeming her as animal like and the type of woman to run men away. I don’t think it lightened the blow to see Martin’s real-life wife as light as Gina.

Now let’s really talk: Pam and Gina. For five years viewers watched as Gina (played by Tisha Campbell) was the kind, beautiful, light-skinned, sought-after and perfectly silly partner of Martin. On the other hand there was Pam; (played by Tichina Arnold) dark-skinned, loud and confrontational, though still attractive. Gina was the love interest to the main face of the series, while Pam was simply Gina’s combative best friend. Pam’s relationship with Martin was playfully explosive, with the two consistently making fun of each other. Martin consistently referencing Pam’s “bad attitude,” “nasty mouth,” “buck-shots;” while also deeming her as animal like and the type of woman to run men away. I don’t think it lightened the blow to see Martin’s real-life wife as light as Gina.

Don’t get it twisted. Martin is a respectable classic, whose re-runs we all love. You just can’t help but to point out the aesthetics that speak to a harsh reality within the black community.

Some people will say the portrayals stand without colorism and remain true to some woman who fits the description of the character, but the underlying issue is variation!!!!!

The last instance of colorism I’d like to point out is one that goes against what we typically see as “colorism”: The Hillary Banks (Fresh Prince): light in complexion, self-centered, air-head that can never do right. The Dionne Davenport (Clueless): light-skinned, knowingly beautiful, rich girl who prefers not to use her popularity for good cause. Whitley Gilbert (A Different World): snobby as hell, though she eventually mellowed out. Regine Hunter (Living Single): image-conscious, materialistic and men loving. Could these portrayals of “air-headed” lighter toned women be some sort of “revenge” for society’s seemingly admiration for lighter skinned black women.

The last instance of colorism I’d like to point out is one that goes against what we typically see as “colorism”: The Hillary Banks (Fresh Prince): light in complexion, self-centered, air-head that can never do right. The Dionne Davenport (Clueless): light-skinned, knowingly beautiful, rich girl who prefers not to use her popularity for good cause. Whitley Gilbert (A Different World): snobby as hell, though she eventually mellowed out. Regine Hunter (Living Single): image-conscious, materialistic and men loving. Could these portrayals of “air-headed” lighter toned women be some sort of “revenge” for society’s seemingly admiration for lighter skinned black women.

These instances of colorism have us feeling combative towards our own sisters. Dark-skinned women consistently feeling as if their chocolate skin makes them less attractive or even less acceptable. As well as light-skinned women feeling as if their complexions forbid them from having a real seat at the table.

Skin should never be the deciding factor to how anyone feels or views about another person. Just as black Americans want white people to quit stereotyping them, we in the black community have to quit stereo-typing and disqualifying one another.

Note: I think it also important for light-skinned women to acknowledge their particular privilege and USE IT when combatting issues of racism.

-Tysheira Scribner

June 3rd, 2009 marked the demolition of the last public housing project in Atlanta. Bowen Homes, built in 1964 and located on the west side of Atlanta, housed almost 1,000 people and was the last large family housing project left in Atlanta until its demolition. The end of Bowen Homes marked the end of a controversial program. In turn, it started a controversial debate about Atlanta and gentrification. The Atlanta Housing Authority’s executive director hailed the demolition as an event that “marks the end of an era where warehousing families in concentrated poverty will cease.”[1] Former residents of demolished projects had a multitude of reactions: most were of hurt and confusion, with one Bowen Homes resident stating, “This is just wrong. I wish I could join in with their rejoicing. I can’t.”[2] The demolition of public housing in Atlanta created a diaspora for groups of African Americans in Atlanta. What started happening over 20 years ago in the mid-1990’s has had ramifications to this day. To fully grasp why this debate is occurring in Atlanta (and many other American cities), it is worth examining the roots of the system that was put in place; in turn, we can examine ways to avoid previous pitfalls and create safer, more equitable neighborhoods in Atlanta and beyond. What seems to be lost in this debate are human lives affected. Where do the residents go, and how are they being helped in the long term?

Atlanta is a city of transplants. People from all over have moved to “the city too busy to hate” in the last 30 years—in fact, Atlanta gained the fourth most new residents of any American city in 2017.[3] There are few traces of the former projects—if they haven’t been converted into new apartments, they have been wholly demolished. Built in 1936 and once occupying the current location of Atlantic Station, Techwood Homes was the first housing project built in America.[4] Ironically enough, Techwood Homes was built over a part of town known as The Flats, a low-income neighborhood with a sizable African American population. Hailed as an opportunity to erase slums, increase affordable housing, and improving the overall landscape of the city, Techwood Homes and the other Atlanta housing projects came to represent a failed housing policy that left people behind, and the people left behind were African American.

By the 1996, Atlanta was the first city in the United States to commence demolishing its housing projects. By that time, Atlanta had a greater percentage of residents living in public housing than any other city in the United States.[5] The demolition of the housing projects did not mean that public housing ended in Atlanta. Mixed-income communities and government-sponsored Section 8 housing were created; still, the toll on the projects’ former residents was not taken into account. Having to qualify for vouchers, find affordable housing, and often moving to only slightly less impoverished neighborhoods does not fix the problem of housing inequality. In a volatile or down economy, public housing demolitions can lead to homelessness if more low-income housing is not made available.[6] Furthermore, the vouchers provided to former residents are often looked upon with suspicion by their new landlords—the vouchers also restrict people with criminal backgrounds from obtaining them.[7] Following the demolition of the projects, a large majority of displaced residents settled in 10 of Atlanta’s poorest ZIP codes thus re-creating a cycle of poverty.[8] In fact, a 2011 Georgia State University survey found that most residents ended up in new places within, on average, only three miles of their former homes.[9]

The winners of this demolition are the contractors and investors. Once a neighborhood has gentrified, real estate values sky-rocket and money is made. At what cost? Culture has been wiped out at the expense of condos and Beltline apartments. Poor African Americans who have lived in a neighborhood their entire lives are told to pack and handed a check that will not cover a move to a safer part of town. Housing projects certainly centralized crime but to demolish them and not provide affordable housing for all merely exacerbates their original problem: legalized segregation. Conversations about gentrification and government-mandated segregated housing are finally being discussed by the mainstream. In fact, the founder of the Atlanta Beltline project recently resigned due to a belief that his project was not providing enough affordable housing and promoting inequitable gentrification.[10] What has been done at East Lake Meadows is another model that combats gentrification by preserving the neighborhood through a construction project. Realization and self-awareness by the Beltline project creator and developer Tom Cousins are what will ultimately will help those affected by gentrification. Until then, real estate will continue to take precedent over a city’s citizens.—Jeff Brown

[1] Mark Niesse, “Census: Metro Atlanta’s population approaches 5.8 million,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, April 18, 2017. https://www.ajc.com/news/local-govt–politics/census-metro-atlanta-population-approaches-million/1pxSPBRYI6L26zn4jgVBrN/.

[2] Niesse, “Census.”

[3] Niesse, “Census.”

[4] Robbie Brown, “Atlanta Is Making Way For New Public Housing,” The New York Times, June 20, 2009. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/21/us/21atlanta.html.

[5] Brown, “Atlanta.”

[6] Brown, Atlanta.”

[7] Brown, Atlanta.”

[8] Brown, Atlanta.”

[9] Stephanie Garlock, “By 2011, Atlanta Had Demolished All of Its Public Housing Projects. Where Did All Those People Go?” City Lab, May 8, 2014. https://www.citylab.com/equity/2014/05/2011-atlanta-had-demolished-all-its-public-housing-projects-where-did-all-those-people-go/9044/.

[10] Leon Stafford and Willoughby Mariano, “Beltline CEO steps down; New head to focus on affordable housing,” The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, August 23, 2017. https://www.myajc.com/news/local-govt–politics/beltline-ceo-steps-down-new-head-focus-affordable-housing/RoWS3022b1qYl8eWAoBa6M/.

"I am the first and the last. I am the honored one and the scorned one. I am the whore and the holy one. I am the wife and the virgin. I am the barren one and many are my daughters. I am the silence that you can not understand. I am the utterance of my name." Nana Peazant (Daughters of the Dust), via The Thunder, Perfect Mind

It was through this incredible 90s seminar that I was introduced to Julie Dash and Daughters of the Dust. I thought to myself, “this looks like Beyoncé’s video.” In fact, the year that Mrs. Knowles-Carter dropped her historic Lemonade visual album marked the 25th anniversary for Daughters of the Dust, as well as a seemingly pivotal time in defining and accepting black identity; I don’t think it happened coincidentally.

Daughters of the Dust tells a compelling story of a self-preserved Gullah Island family who overtime, has been able to maintain their ancestor’s unique culture. They are the direct descendants of the slaves who worked the area. The film is packed with tradition and gives a new meaning to perseverance. However, after many years, much of the Peazant family has decided to move into the “mainland.” This manifestation of assimilation into mainstream and modern culture is a major theme throughout the film. While the matriarch of the family, Nana, would probably never give the mainland the time of day, others are willing to part ways with tradition in hope of easier life. What they don’t realize however, is that mainland life isn’t as glorious as it appears. (As evident in the return of Yellow Mary)

I began to think about black identity, specifically, black American identity. I can’t be the only one who has felt as if black Americans, to Africans, are another rendition of the light-skinned versus dark-skinned beef. Again, it brings me to question what black identity really is, what it isn’t, and who gets to make these decisions?

Maybe we are struggling so much in determining black identity because for once, we are peaking out of the veil and feeling the need to define ourselves, for ourselves. Daughters of the Dust offers a revelation that the antagonist of their black Gullah identity is influence of European culture. (The mainland) This could explain why blacks from Africa often disregard black American’s as their own, due to American influence in our black American culture. This also helps to explain the dark-skinned versus light-skinned beef, as lighter-skin is too often associated with European relation.

So…I paint the question to you; what really is black identity? Sociologist have long said that race, “black” and “white” are merely social constructs but with what identity does that leave the entire black race when we consistently label the assets of our identity with the inclusion of the word “black”?

Could it be possible that identifying black culture begins with embracing, understanding, and breaking down what it means to be African American? Both African. And American.

I believe America’s war on black people makes it difficult for us to want to identify ourselves as pieces of them, but truth be told, we are. Also, and not to be confused with assimilation, maybe we can come to consider ourselves as the evolved versions of our ancestors. Not to get evolution confused as being “advanced,” but rather “a new model fit for its circumstances.”

What Daughters of the Dust offers us is a chance at witnessing a facet of our African American culture.

Let us consider long gowns in modesty, oversized hats, Sunday’s best with ruffles, white lace and a small dose of sheer, capable of bearing imagination. Let us consider traditional names that speak to our being, and a tongue that makes love with the creole. Let us embrace, and not abuse family; “Eli, your wife does not belong to you, she only married you.” And for our women, embrace your independence, “for it fine to want a man to depend on for only if you need to.” Embrace nature around you and the organics things nature give to you. Try fresh gumbo and weaving baskets.

Let your hair be the feelings that you wear; brief or long, twisted or puffed, free or tamed. To be sassy in demeanor is ok, enthralled with the spirits of your ancestors, but always in love and protection. If you shall dance, dance; Practice your footwork, let your arms go and let your body tell its message. Be spiritual; in whole like your hopped jewelry. Love and respect thy elders in a way the master respected thy whip.

Too, the pieces of this very archive, the years surrounding it, the historical black American events, trials and tribulations, further aid in the quest to define our African American identities.

On this 27th anniversary of Daughters of the Dust, I consider preservation, multiculturalism and evolution. From the time I began to learn in depth about black American identity I felt that black Americans must have it the hardest. Because truly, we are African and truly, we are American. One must come to a place of balance, a place of love, two seemingly polarized identities in which you’ve been birth. Without the impact of this social construct of what”blackness” means to our European counterparts, the African and the America represents the true essence of double consciousness. (As defined by Du Bois)

-Tysheira Scribner

More To Ponder: In defining black and African American identities Daughter’s of the Dust can give us insight on assimilation as a negative occurrence. I think it is important to note that as African Americas, we are not assimilated, yet more so of heterogeneous nature.