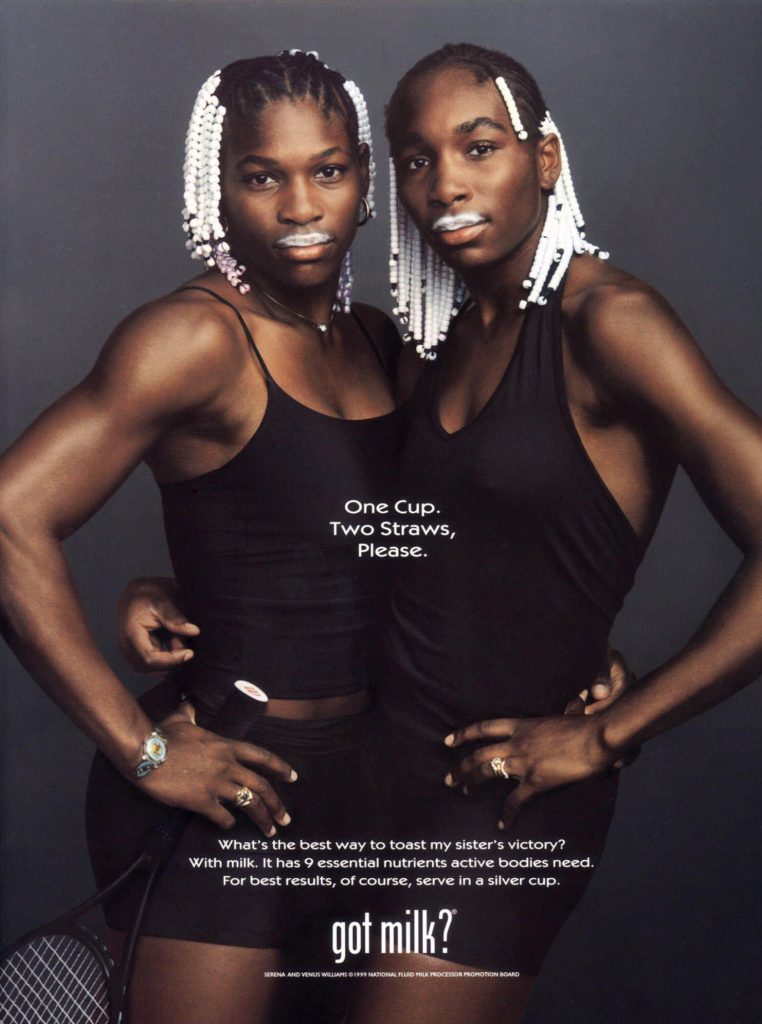

With big smiles and several tiny braids adorned with colorful beads, the Williams sisters arrived on the tennis courts that never saw them coming. Legend (and a snippet from an E! True Hollywood Story) has it that their father Richard, who worked security before the sisters were born, once watched the winner of a women’s tennis match collect a check for more money than he’d ever made and prophesied his future daughters’ domination of the tennis world. He trained them on courts near their home in Compton, California – the same hood where those O.G.s of Gangsta Rap, Dr. Dre and Snoop, put both their raps and their macks down.

But, well, back to the lecture at hand.

Serena, Venus, and their five siblings were raised as Jehovah’s Witnesses in a part of Compton that didn’t make it to music videos: the wholly unglamorous one-story homes with picket fences surrounding small backyards. The Williams family led a fairly routine, “normal” life which included several hours of early morning tennis practice followed by home-school lessons. In a brazen move, while affluent parents sought expensive and exclusive lessons for their future tennis champions, Mr. Williams initially coached the girls himself after teaching himself the game via instructional videos. This tension between the carefully crafted game of prestige and the scrappy, can-do attitude of the Williamses played out in myriad ways, some nuanced and some blatant.

The Williams Sisters – Their Rise to Fame

Williams continued to coach the girls, only sending the girls to Brentwood coaches and tennis academies every now and then, and he boldly chose to keep his daughters out of the junior tennis circuits, where products of elite training schools competed for press and notoriety. The Williams Sisters’ sudden appearance on the courts seemed to shock the country club crowd that didn’t seem previously exposed to such… diversity.

They were viewed by some as disrespectful disturbers of the tennis circuit’s norms. Their powerful strength game visibly differed from the precision and speed game the beiger players had meticulously cultivated, and their absence from the prep schools and junior tournaments appeared to confirm their lack of “proper” training and etiquette.

Several platforms sustained efforts to subtly critique sisters’ background, family bond, dress/hair style, athletic strength. The intense media surveillance of them almost seemed determined to “keep an eye” on what was considered a threat. The media tried to downplay the sisters’ major achievements, their contributions to the black community, and their obvious inherent talent. But neither Venus nor Serena made an effort to hide signifiers of black culture and style, like braids, or their cultivation of outside interests, and the black community often voiced praise of the young women who had already broken barriers just by stepping onto those courts and appearing in the news articles which noted black talent, black excellence, and just overall black girl magic.

Even as they faced criticism from their peers for being aloof and daring to pursue educations, they quickly caught Corporate America’s attention and signed lucrative endorsement deals, one with Reebok for $12,000, 000 over five years.

The family continued on The Glow Up (that Concept Formerly Known as The American Dream): Venus was representing international brand, they bought a mansion in Florida with its own tennis courts, and the girls started to attend a noteworthy private school. The Williams were following the footsteps of Althea Gibson, who was the only African-American woman to win a Grand Slam title before Venus and Serena basically won the 90’s – they won their first Doubles title in 1998 and the U.S. Open Doubles title in 1999, the same year Serena defeated longtime champion Martina Hingis to win the U.S. Open Grand Slam. Their international tennis rankings skyrocketed; their investments of time and hard work were finally paying off, and they would eventually continue on to win the 00’s. But performing on a larger stage brought even more visible racist sentiments to the forefront.

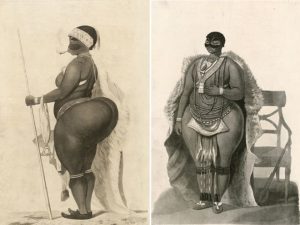

Serena, in particular, was routinely attacked for qualities white culture has often attributed to black women. In the 1800s, Saartjie Baartman (“Hottentot Venus”), a South African woman, was brought to London in 1810 as a symbol of racial difference (and the supposed superiority of white beauty) and placed in a circus display alongside conjoined twins, dwarfs, and other alleged “deviants.”

“… Hottentot was assigned the role of a creature bridging human and animal realms” (Strother, 4).

According to their father, the Williams sisters were trained to be “warriors,” “attack dogs.” But the media and several tennis enthusiasts ridiculed and chastised them for their “beast-like” physical appearances, “lewd” athletic wear, and “angry” outbursts. They tended to characterize Serena and Venus using some of the most common stereotypes of black women: overly sexualized women (who chose to wear outfits they liked whether or not those clothes highlighted physical features that tennis viewers were not used to seeing) and angry black women (who dared to express basic human emotions like frustration without wearing a mask to protect the “delicate” sensibilities of an audience famous for its dignified silence and barely audible clapping).

During the 1997 U.S. Open Women’s Singles Semi-Final match between an unseeded Venus and an 11th-seeded Irina Spirlea, both players bumped into each other as they customarily switched sides during a changeover. Williams said neither of them were looking where they were going; Spirlea said she expected Venus to move out of the way.

Venus Williams_Irina Spirlea US Open “Bump”

“She’s not going to turn … I’ve done it all the time, I turn. But she just walks. I wanted to see if she was going to turn. She didn’t.” – Irina Spirlea (This is the clean version of the quote. Make your best guess for which obscenity she used to describe Venus.)

Such inane controversies were veiled attempts to subdue the sisters who would routinely take long breaks from the game, only to come back stronger and more determined to embarrass those who underestimated them.

Venus and Serena continue to raise questions about what it means to be feminine, beautiful, strong, black, successful, wealthy, and sisters; despite their numerous successes, they also unfortunately still encounter racism, forcing them to boycott tournaments and defend themselves when they choose to finally fight back. Their eagerly and bitterly watched debut in the 90’s served as a harsh reminder that the black athleticism which white audiences celebrated on basketball courts and football fields did not translate to women’s sports, especially one which still requires its players to dress in all white for certain tournaments. But their exuberance in play and dignity in the face of charged attacks and elitist snubbing also won them many fans who finally saw themselves represented in uncharted territory.

— Radhika Nataraj

Works Cited

- Alexander, Rachel. “Open Final Lands on Venus.” Washington Post, 6 Sept. 1997, p. B1.

- Bass-Adams, Valerie N., Keisha L. Bentley-Edwards, Howard C. Stevenson. “That Not the Me I see on TV…! African American Youth Interpret Media Images of Black Females.” Women, Gender, and Families of Color, vol. 2, no. 1, 2014, pp. 79-100.

- Douglas, Delia. “Venus, Serena, and the Inconspicuous Consumption of Blackness: A Commentary on Surveillance, Race Talk, and New Racism(s).” Journal of Black Studies, vol. 43, no. 2, 2012, pp. 127-45.

- Hobson, Janell. “The ‘Batty’ Politic: Toward an Aesthetic of the Black Female Body.” Hypatia, vol. 18, no. 4, 2003, pp. 87-105.

- Strother, Z.S. “Display of the body Hottentot.” Africans on Stage, Indiana UP, 1999, pp. 1-

- Wright, Joshua. “Be Like Mike? The Black Athlete’s Dilemma.” Spectrum: A Journal on Black Men, vol. 4, no. 2, 2016, pp. 1-19.