“What’s crackin cuz?”

“What’s poppin blood?”

Depending on your location, situation, and ability to understand gang-related terminology, your answer to these questions could determine if you lived or died on certain streets in the 1990s. During that decade, a language that many outsiders interpreted as young urban slang came to signify real insider knowledge, especially at a time when urban youth increasingly defined themselves by street cred, street cred by street violence, and street violence by gang violence, which in turn, became mass mediated gang wars.

From Los Angeles to Little Rock, gang activity experienced a surge across the United States in the early 1990s. This is particularly true of the Southern region. According to a 2010 government History of Street Gangs in the United States, “the southern region led the nation in the number of new gang cities, a 32 percent increase” from the 1970s through the 1990s. By 1998, the South had more states reporting gang problems than any other region in the nation. In fact at the time, this made the South look like it was catching up with the West, Midwest, and Northeast in terms of gang activity.

One HBO documentary from 1994 attempted to capture this spike in southern gang activity as it was felt in Little Rock, Arkansas, of all places. Director Mark Levin’s footage of Hoover Folk, Crip, and Blood gang member initiation rituals, ceremonies, and their groups’ deadly impact on children in a small city shocked the nation. Levin tracked this impact by following Steve Nawojczyk, the Pulaski County coroner at the time (and still-active community leader for inner city youth), to portray a sad state of affairs for Little Rock, and by extension, a narrative of decline for small cities in the South that were similarly affected by gang violence.

What’s interesting about this documentary is how it leads with a largely white, racially and sexually integrated set of Chicago’s Hoover Folk, showing its teenage members sitting in public parks around Little Rock, listening and singing along to Tupac, while later “beating in” a young woman who wants to be initiated. The priorities laid out in this sequence of events are clear: young white kids are being influenced by rap music, and they’re doing violence to one of their white female peers.

This sequence follows a familiar pattern, one well-known among the American black community—a pattern where young white kids are portrayed in the media as being corrupted by the influence of black American communities where “all the trouble started.” The documentary participates in this narrative by telling the story of a slightly older black men who came up in the Crip and Blood scene of Los Angeles, but later moved to Little Rock in the 1980s, where the documentary suggests the man becomes a major kingpin of that city’s 1990s gang scene.

Gang War: Bangin’ in Little Rock is unique in its mass mediated portrayal of gang violence affecting white urban youth in a small city, but its subtle portrayal of the American black community as the root of such violence is all-too-familiar. Throughout the early 1990s, movies, television, music and documentaries engaged in a systemic pattern of portraying gang-related crime, gang violence, and gang wars in ways that made that violence look peculiar to American black communities, especially black youth in the inner cities of Los Angeles and New York City. We can see such depictions most readily in movies like Boyz in the Hood (1991) and New Jack City (1991), which show young black men struggling to survive gang violence within their predominantly black neighborhoods in Los Angeles and New York City, respectively.

Then on television and again in 1991, national and international audiences witnessed the initial filming and eventual fallout from the Rodney King beatings in the form of the LA Uprising, whose television news coverage repeated the same systemic pattern of negatively portraying black communities as hotbeds of criminal and gang-related activity. Filtered through an implicit bias about violence on the West Coast—which we also see iterated in the Little Rock documentary when Levin focuses on the city’s supposed kingpin from LA—this event took place in Los Angeles, where the violent video images of white LAPD officers viciously beating the young black King within an inch of his life were broadcast and looped on national news networks for over a year between 1991 and 1992.

Perhaps one day, we will regard this “beat-in” as the horrific act of gang violence it actually was.

But what isn’t often remembered in mainstream accounts of the LA Uprising (an event formerly called the “LA Riots”), which directly followed the acquittal of the white LAPD officers who beat Rodney King, is that it was directly preceded by the Watts Truce between Crip and Blood gangs in 1992. Gangs such as the Crips and Bloods had been around for your years before the decision to call the 1992 truce, and issues of police brutality and racism was not the only thing that led to the truce. Active and non-active gang members on both side had realized how much destruction they had caused on their own neighborhoods. For a short period of time, there seemed to be some end to the madness that was brewing between two rival gangs. Entertainers such as Snoop Dogg and football legend Jim Brown were both vocal about keeping the peace. Here, we see black entertainers (mostly rappers and activists), highlight the possibilities of representing black people in a more positive light.

And yet just days after this small armistice and positive media coverage, the LA Riots, or what many now consider the LA Uprising, began after the white police officers who beat Rodney King were acquitted of their crimes. From television news coverage of looting to beatings in the street, the Uprising had people around the nation tuned into the their TVs to see what was going on in LA. And although Watts Truce was still fresh, there was resurgence of violence between the groups because of the LA Riots. Both gangs used the time of chaos to attack each other which ultimately destroyed what many had hoped would end the violence between the two.

However, while short-lived and a little too early, the Watts Truce sent a powerful message, not only to white Americans, but also to black Americans, that change was possible if mortal enemies united against much larger common enemies, such as police brutality and racist media coverage. In Black Looks (1994), bell hooks explains why such racially biased mediations exist by calling attention to their (mostly white) American mainstream audience, which has an implicit, complicit, perverse, and voyeuristic desire to observe representations of black men’s bodies being assaulted by “white racist violence, black on black violence, the violence of overwork, and the violence of addiction and disease” (34). Indeed, it should come as little surprise that both movies and television—two forms of media that are most often made with that mainstream, mostly white audience at the time—reinforce these stereotypes.

So from New York to LA to Little Rock, the 90s were a unique period in the history of representation of black culture in the United States. Indeed, the LA gang peace treaty and the LA Uprising were critical events in that history: one that, if we listen only to 90s media, is simply a story of gang wars and occasional peace treaties that largely affected African American communities. However, if we listen more closely, particularly to the voices of those communities, we might, sometime in the future, begin to hear how to avoid repeating mistakes of the past.

One of those voices comes from West Coast rapper Kam, who might have said it best in his 1993 song “Peace Treaty.”

— Andy Reid and Joshua Ryan Jackson

Works Cited

hooks, bell. Black Looks: Race and Representation. South End P, 1992.

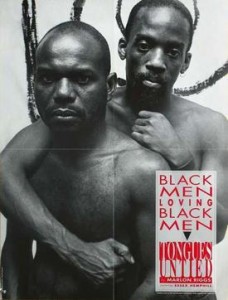

narrative accounts via its director, Marlon Riggs, with fictional vignettes and interpretive poetry that represent a collective yet varied and mutable black, gay identity. The docufilm focuses primarily on gay black men (e.g. Essex Hemphill, Joseph Beam, Craig Harris and Riggs himself) , who also openly and unapologetically confront the ugly heads of racism and homophobia. Scenes of clips from homophobic stand up routines (e.g. by Eddie Murphy) and of the Civil Rights Movements serve to combat negative stereotypes and link the struggles of black, gay men with an historical legacy of resistance. Undoubtedly, “Tongues Untied” is focused and political in its thrust, arguably more so than “Paris is Burning.” Unlike Livingston, Riggs chooses not only to depict men stymied under the weight of white supremacy, but also takes the system to task, illustrating instances of fierce opposition. One such oppositional method is the refutation of silence preluded by the film’s title. Riggs directly challenges this inclination towards silence, not in a way that begets shame (he focuses his critique on a society that promotes and demands speechlessness), but rather one that privileges the power of black, gay men’s voices. Undoubtedly, herein lies the revolutionary mark of “Tongues Untied.”

narrative accounts via its director, Marlon Riggs, with fictional vignettes and interpretive poetry that represent a collective yet varied and mutable black, gay identity. The docufilm focuses primarily on gay black men (e.g. Essex Hemphill, Joseph Beam, Craig Harris and Riggs himself) , who also openly and unapologetically confront the ugly heads of racism and homophobia. Scenes of clips from homophobic stand up routines (e.g. by Eddie Murphy) and of the Civil Rights Movements serve to combat negative stereotypes and link the struggles of black, gay men with an historical legacy of resistance. Undoubtedly, “Tongues Untied” is focused and political in its thrust, arguably more so than “Paris is Burning.” Unlike Livingston, Riggs chooses not only to depict men stymied under the weight of white supremacy, but also takes the system to task, illustrating instances of fierce opposition. One such oppositional method is the refutation of silence preluded by the film’s title. Riggs directly challenges this inclination towards silence, not in a way that begets shame (he focuses his critique on a society that promotes and demands speechlessness), but rather one that privileges the power of black, gay men’s voices. Undoubtedly, herein lies the revolutionary mark of “Tongues Untied.”