"I am the first and the last. I am the honored one and the scorned one. I am the whore and the holy one. I am the wife and the virgin. I am the barren one and many are my daughters. I am the silence that you can not understand. I am the utterance of my name." Nana Peazant (Daughters of the Dust), via The Thunder, Perfect Mind

It was through this incredible 90s seminar that I was introduced to Julie Dash and Daughters of the Dust. I thought to myself, “this looks like Beyoncé’s video.” In fact, the year that Mrs. Knowles-Carter dropped her historic Lemonade visual album marked the 25th anniversary for Daughters of the Dust, as well as a seemingly pivotal time in defining and accepting black identity; I don’t think it happened coincidentally.

Daughters of the Dust tells a compelling story of a self-preserved Gullah Island family who overtime, has been able to maintain their ancestor’s unique culture. They are the direct descendants of the slaves who worked the area. The film is packed with tradition and gives a new meaning to perseverance. However, after many years, much of the Peazant family has decided to move into the “mainland.” This manifestation of assimilation into mainstream and modern culture is a major theme throughout the film. While the matriarch of the family, Nana, would probably never give the mainland the time of day, others are willing to part ways with tradition in hope of easier life. What they don’t realize however, is that mainland life isn’t as glorious as it appears. (As evident in the return of Yellow Mary)

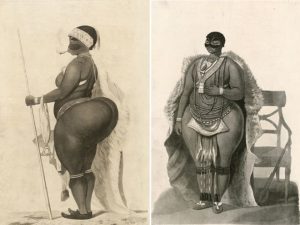

I began to think about black identity, specifically, black American identity. I can’t be the only one who has felt as if black Americans, to Africans, are another rendition of the light-skinned versus dark-skinned beef. Again, it brings me to question what black identity really is, what it isn’t, and who gets to make these decisions?

Maybe we are struggling so much in determining black identity because for once, we are peaking out of the veil and feeling the need to define ourselves, for ourselves. Daughters of the Dust offers a revelation that the antagonist of their black Gullah identity is influence of European culture. (The mainland) This could explain why blacks from Africa often disregard black American’s as their own, due to American influence in our black American culture. This also helps to explain the dark-skinned versus light-skinned beef, as lighter-skin is too often associated with European relation.

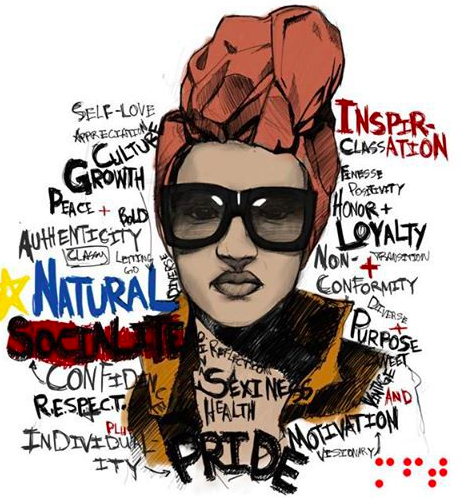

So…I paint the question to you; what really is black identity? Sociologist have long said that race, “black” and “white” are merely social constructs but with what identity does that leave the entire black race when we consistently label the assets of our identity with the inclusion of the word “black”?

Could it be possible that identifying black culture begins with embracing, understanding, and breaking down what it means to be African American? Both African. And American.

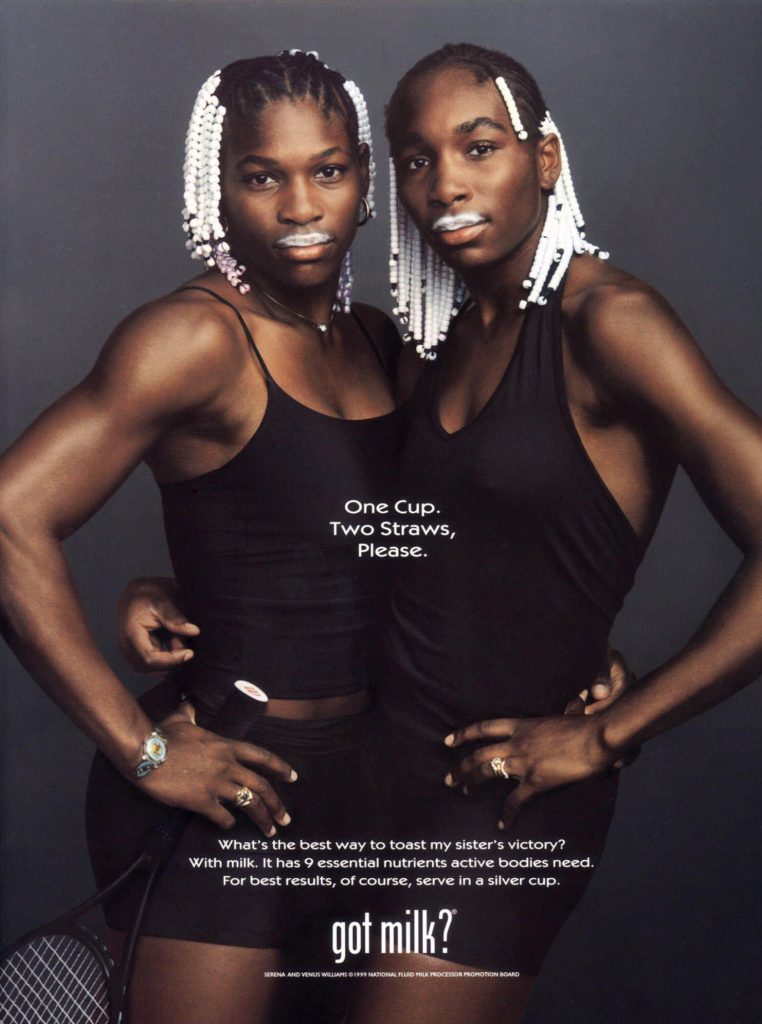

I believe America’s war on black people makes it difficult for us to want to identify ourselves as pieces of them, but truth be told, we are. Also, and not to be confused with assimilation, maybe we can come to consider ourselves as the evolved versions of our ancestors. Not to get evolution confused as being “advanced,” but rather “a new model fit for its circumstances.”

What Daughters of the Dust offers us is a chance at witnessing a facet of our African American culture.

Let us consider long gowns in modesty, oversized hats, Sunday’s best with ruffles, white lace and a small dose of sheer, capable of bearing imagination. Let us consider traditional names that speak to our being, and a tongue that makes love with the creole. Let us embrace, and not abuse family; “Eli, your wife does not belong to you, she only married you.” And for our women, embrace your independence, “for it fine to want a man to depend on for only if you need to.” Embrace nature around you and the organics things nature give to you. Try fresh gumbo and weaving baskets.

Let your hair be the feelings that you wear; brief or long, twisted or puffed, free or tamed. To be sassy in demeanor is ok, enthralled with the spirits of your ancestors, but always in love and protection. If you shall dance, dance; Practice your footwork, let your arms go and let your body tell its message. Be spiritual; in whole like your hopped jewelry. Love and respect thy elders in a way the master respected thy whip.

Too, the pieces of this very archive, the years surrounding it, the historical black American events, trials and tribulations, further aid in the quest to define our African American identities.

On this 27th anniversary of Daughters of the Dust, I consider preservation, multiculturalism and evolution. From the time I began to learn in depth about black American identity I felt that black Americans must have it the hardest. Because truly, we are African and truly, we are American. One must come to a place of balance, a place of love, two seemingly polarized identities in which you’ve been birth. Without the impact of this social construct of what”blackness” means to our European counterparts, the African and the America represents the true essence of double consciousness. (As defined by Du Bois)

-Tysheira Scribner

More To Ponder: In defining black and African American identities Daughter’s of the Dust can give us insight on assimilation as a negative occurrence. I think it is important to note that as African Americas, we are not assimilated, yet more so of heterogeneous nature.