“One truism in life, my friend…When that jones come down, it be a mothafucka.”- Savon Garrison

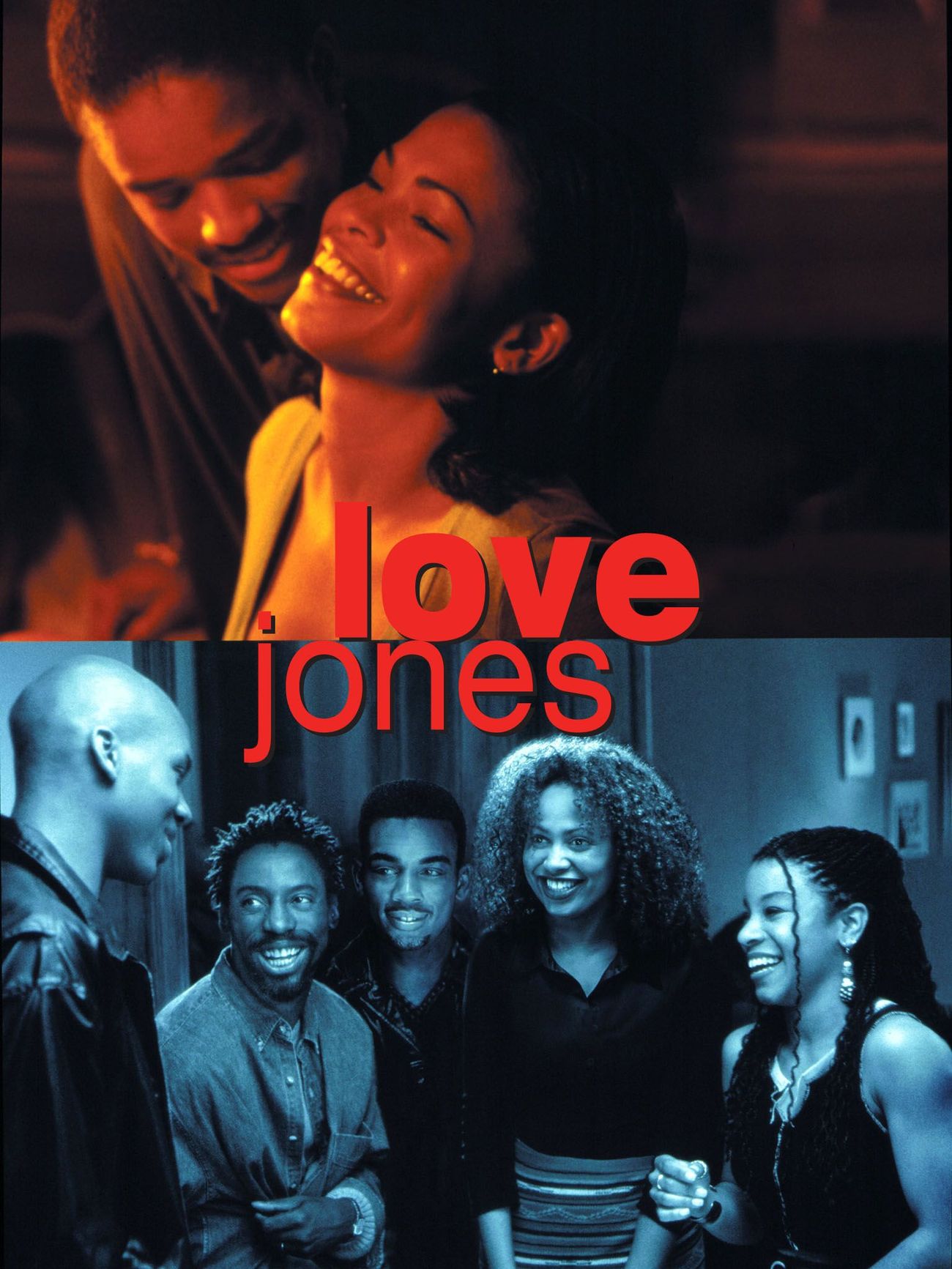

This line from the cult classic Love Jones is what best describes how this movie has influenced Black love and Black-romantic comedies twenty-one years since it’s opening on March 14, 1997. Love Jones premiered as a new twist and imagery of Black love and Blackness on cinema. The director, Theodore Witcher, a Chicago native, describes Nina and Darius as being a part of the “creative class”[i]. This class highlights a nuanced representation of Black people in the mid-90s who were college educated and were interested in the arts. Coming up behind classic hood movies such as Poetic Justice (1993), Friday (1995) and Juice (1992), Love Jones paved the way for writers and directors to create movies that highlighted Black people who were academically successful and in love.

In 2017, the cast and crew of the film came together for the LA Time’s oral history conversation to honor the 20th anniversary of the film and to talk about the authenticity of the movie, the beauty of the soundtrack and the impact of Black love being caught on film. Coincidentally, the film was honored last year at the American Black Film Festival Awards and received the award for “Class Cinema Tribute”. The award and oral reflection proves that Love Jones is a classic film that transcends through Black cinematic history. While Love Jones provided its very nostalgic lines and scenes, Love Jones painted Black love and friendship in a way that was artistic and creative in nature. Julia Chasman, the executive producer of the film explained that the script presented the lives of young Black artist in Chicago that was normally seen in white movies [ii].

Because of Witcher’s simplicity in his attempts to create a romantic comedy that explored the relationship between two artists in Chicago, he was able to pair the movie with a phenomenal soundtrack. The Love Jones soundtrack was released four days before the film and peak at number three on the Billboard Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums in 1997 [iii]. This soundtrack contained classics such as “The Sweetest Thing” by Lauryn Hill, “Sumthin’ Sumthin’” by Maxwell and “In a Sentimental Mood” by Duke Ellington and John Coltrane. The soundtrack has a mixture of iazz, neo-soul, R&B and poetry that reflects the artistic attraction that the film provides. The soundtrack actually prompted the studio to re-release of Love Jones five months after its debut in theatres because people loved the soundtrack so much [iv].

Although the film didn’t do spectacularly at the box office, Love Jones put two actors together that showed a dynamic depiction of Black love and sexuality that was liberating and visually stunning. Ironically, both Nia Long and Larenz Tate were not Witcher’s first choice, but New Line Studios suggested Tate and one of the executive directors suggested Long [v]. After a few meets and readings, the chemistry between Tate and Long proved that they were best for the part. Nia Long said; “I honestly felt like our chemistry was the best. It felt amazing and it felt right, and we looked good together and it looked believable.” [vi]

Love Jones presented viewers a new image of Black love on screen that showed two Black people who were young intellectuals who had a carefree way of loving each other. I believe that the cast would agree that Love Jones was definitely a movie before it’s time. However, over time, the movie became one to be appreciated due to is jazz undertones, references to Gordon Parks, the bond with poetry and spoken word in urban Chicago. This movie paved the way for more narratives of middle-class Black love in similar movies such as The Best Man, Love & Basketball, and Brown Sugar. So, thank you Love Jones for being a movie that I can laugh to, cry and fall in love with for 21 years and 21 more years to come. And that’s urgent like a muthafucka. —Adeerya J.

Citations

[i]http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/movies/la-et-mn-love-jones-oral-history-20170313-htmlstory.html

[ii]https://www.villagevoice.com/2018/02/12/theodore-witcher-talks-love-jones-21-years-later-and-why-he-hasnt-made-a-follow-up/

[iii] ibid.

[iv] ibid.

[v] ibid.

[vi] ibid.