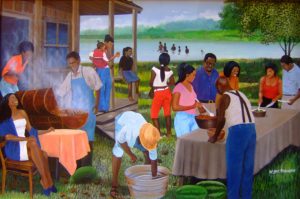

When I think about my summers in Atlanta, I think about going to various cookouts my parents used to take me and my sister to when we were younger. They were either their close friends or co-workers who always welcomed my family with great BBQ, fun games and plenty of music and dancing. It’s amazing that Black people possess the creativity and dancing skills that shape dance culture in the Hip-Hop world. Some of my favorite dances came from the 90s, especially memories of having booty shaking (aka twerking) battles with my friends at summer camp and trying to do the Tootsee Roll on roller skates.

When I think about my summers in Atlanta, I think about going to various cookouts my parents used to take me and my sister to when we were younger. They were either their close friends or co-workers who always welcomed my family with great BBQ, fun games and plenty of music and dancing. It’s amazing that Black people possess the creativity and dancing skills that shape dance culture in the Hip-Hop world. Some of my favorite dances came from the 90s, especially memories of having booty shaking (aka twerking) battles with my friends at summer camp and trying to do the Tootsee Roll on roller skates.

I’ve always had a love for dancing, so when my favorite song, “C’mon N’ Ride It” by the Quad City DJ’s came on at the cookouts I was ready to show out. I would begin to bounce my shoulders, roll my arms and rock side-to-side in a rhythmic fashion and proceed to ride the train. This dance was closely similar to the popular Southwest Atlanta dance, the Bankhead Bounce originating in the Bankhead neighborhood. The original song that the Bankhead Bonce originated from was performed by an Atlanta rapper named Diamond and featured D-Roc in 1996 [i]. This dance required a rapid shoulder bounce with hands and fist bouncing in front of you from side to side. This dance could have been performed to any southern Hip-Hop song such as A-Town Players, “Wassup Wassup”, 95 South’s “Whoot! There It Is” and TLC’s Waterfalls, which they performed in their music video in 1995 [ii].

I’ve always had a love for dancing, so when my favorite song, “C’mon N’ Ride It” by the Quad City DJ’s came on at the cookouts I was ready to show out. I would begin to bounce my shoulders, roll my arms and rock side-to-side in a rhythmic fashion and proceed to ride the train. This dance was closely similar to the popular Southwest Atlanta dance, the Bankhead Bounce originating in the Bankhead neighborhood. The original song that the Bankhead Bonce originated from was performed by an Atlanta rapper named Diamond and featured D-Roc in 1996 [i]. This dance required a rapid shoulder bounce with hands and fist bouncing in front of you from side to side. This dance could have been performed to any southern Hip-Hop song such as A-Town Players, “Wassup Wassup”, 95 South’s “Whoot! There It Is” and TLC’s Waterfalls, which they performed in their music video in 1995 [ii].

Most of my early summers were spent at my local Boys and Girls Club. I had a cool group of girlfriends who were always down to dance. So, when one of the camp counselors brought in their mix city with the latest Hip-Hop songs we would rush to the boom box and dance till our moms came to pick us up. A classic was the 69 Boyz, “Tootsee Roll” which actually peaked at the number one spot on the Billboard Hot 100 Rap chart and number eight on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1994 [iii]. This dance was a more inverted funky chicken, which one would wind their knees inward while doing a dip. We also enjoyed the butterfly—similar to the Tootsee Roll, Da Dip by Freak Nasty and any other song that provided us instructions to shake our hips or drop it low.

Most of my early summers were spent at my local Boys and Girls Club. I had a cool group of girlfriends who were always down to dance. So, when one of the camp counselors brought in their mix city with the latest Hip-Hop songs we would rush to the boom box and dance till our moms came to pick us up. A classic was the 69 Boyz, “Tootsee Roll” which actually peaked at the number one spot on the Billboard Hot 100 Rap chart and number eight on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1994 [iii]. This dance was a more inverted funky chicken, which one would wind their knees inward while doing a dip. We also enjoyed the butterfly—similar to the Tootsee Roll, Da Dip by Freak Nasty and any other song that provided us instructions to shake our hips or drop it low.

As a young Black girl, I wasn’t aware of why I was shaking my butt at the young age of eight but similar to the women who were getting’ down at Freaknik or Black Bike Week it was a fun dance to do and you couldn’t resist the beat of the music. Growing up in the era of 2 Live Crew and Uncle Luke, or hearing songs that tell you to “Back that azz up” it’s a dance move that’s hard to refuse. When me and my friends or cousins got together at a family cookout hearing Juvenile’s “Back That Azz Up” really took over for the ’99 and the ’00. With its sexually explicit lyrics demanding listeners to back their ass up on the rapper himself, this song defiantly is a cultural favorite and can still be heard on your local HBCU campus and neighborhood cookouts.

As a young Black girl, I wasn’t aware of why I was shaking my butt at the young age of eight but similar to the women who were getting’ down at Freaknik or Black Bike Week it was a fun dance to do and you couldn’t resist the beat of the music. Growing up in the era of 2 Live Crew and Uncle Luke, or hearing songs that tell you to “Back that azz up” it’s a dance move that’s hard to refuse. When me and my friends or cousins got together at a family cookout hearing Juvenile’s “Back That Azz Up” really took over for the ’99 and the ’00. With its sexually explicit lyrics demanding listeners to back their ass up on the rapper himself, this song defiantly is a cultural favorite and can still be heard on your local HBCU campus and neighborhood cookouts.

The beauty about Hip-Hop is that it has the ability to make listeners feel good and bring people together to have a good time. I have many great memories as I reflect on the times when I used to dance to these songs. Now that I’m older the songs and the dances are quite nostalgic and take me to a place where I remember eating saucy ribs and burgers, smelling hot links on the grill, and bouncy houses in the backyard. Importantly, these dances are still remembered today and when played at parties or clubs now, me and my girls will still get low and do the Tootsee Roll and twerk to Uncle Luke’s “Cap D Comin’”. I just hope that this new generation of Hip-Hop dances continues to provide the same nostalgic memories and blissful feelings that we all grew up with in the 90s. —Adeerya J.

Citations

[i]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bankhead_Bounce

[ii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/95_South

[iii]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tootsee_Roll