Walter Dean Myers is the preeminent author of African American teenage fiction and nonfiction of the 1990’s. Using perspectives that many teens had not read before, Myers’ prose humanizes and refines black characters that are often vilified in literature, film, and television. Myers’ works such as Monster, Slam, and countless biographies of African American visionaries gave access to life stories that many teens had not experienced or did not know existed. Myers was a champion for underrepresented, and it is apparent when reading his books that he wrote for those who did not have a voice. In turn, he inspired a generation of children by telling their stories.

Myers was born in Martinsburg, West Virginia on August 12, 1937. He lived ten miles from the plantation on which his relatives had been enslaved for generations.[1] Myers moved to Harlem four years later, and this is where the majority of his works take place. Myers spoke fondly of his New York upbringing and questioned why some authors did not return to their roots, asking, “What happened to the idea of celebrating a neighborhood and the ordinary people in it? Nobody gives them a voice, but I do.”[2] Myers made it a point to celebrate the ordinary in the inner-city and beyond. His works are not confined to Harlem—his most acclaimed and controversial book is Fallen Angels (1988). Taking place during the Vietnam War, its visceral depictions of the war and raw language got it banned from countless school districts. Building upon that book’s fame, Myers entered the 1990’s as one of the most talked about and controversial teen fiction authors in America.

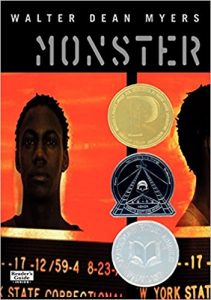

The 90’s marked a plethora of literary awards for Myers. Most notably, he was the runner-up for the Newbery Medal in 1993, runner-up for the National Book Award for Teen Fiction, and was awarded both an American Library Award and a Coretta Scott King Award in 1994.[3] Myers’ most notable work of the 90’s is Monster: A Novel (1999). Myers tells the story of Steve Harmon, a 16-year-old African American from Harlem accused of felony murder. I particularly remember seeing the cover of this book in my Catholic elementary school library. The mugshot of a very dark African American teenager juxtaposed next to the National Book Award sticker makes for a striking cover. The intimidating black felon on the cover is quickly revealed to be a sensitive, shy teenager with a speech impediment, tragically caught in the wrong place at the wrong time. Myers explores black identity throughout the book, with the protagonist writing in his journal after meeting with his lawyer, “I wanted to open my shirt and tell her to look into my heart to see who I really was.”[4] The protagonist tries to reflect goodness and worth in a trying situation. He fears condemnation from other people particularly from his father and white female attorney.[5] Other themes of black identity are prevalent throughout Myers’ other works, namely roots in slavery, uncertainty, and praise of Harlem, America’s “black capital.”[6]

Realistic depictions of injustice, discrimination, transcendence, and hope are Myers’ forte. In fact, Myers wrote over 100 books on a wide array of subjects, from the Iraq War to an African princess.[7] While the majority of his works take place in contemporary times in New York, Myers started writing biographies and historical fiction in the 1990’s. The Glory Field (1994) takes place in 1763 and describes the shackling and transportation of Muhammad Bilal from Sierra Leone to an American plantation; the subsequent story traces the family lineage from his kidnapping to the mid-20th century.[8] The Great Migration: An American Story (1993) “pictures the centrality of scripture-based faith and memories of family members buried in the agrarian South as wanderers make a new life in the urban industrialized North.”[9] Myers even won awards for picture books. Among his most lauded works is Brown Angels: An Album of Picture and Verse (1993). “Brown Angels” reclaims black children from media stereotyping by showing them in child fashions long out of style, reminding the reader “the child in each of us is our most precious part.”[10] Myers’ diverse range of subject matter and genre allowed for a wider audience to consume his books. This expansion of style began in the 1990’s and was one of Myers’ most creative and awarded periods of writing during his career.

A contemporary of Myers, noted children’s author Avi, said “Besides his books, his legacy is a compassionate identity with these young people.”[11]Myers certainly gave a voice to disenfranchised black children and teenagers, writing honestly and compassionately about them. The compassion and honesty he used to describe their experiences made his works appealing to all demographics. Myers’ love and compassion of children from his neighborhood allowed him to transcend target audiences. Myers’ audience is truly anyone willing to take the time and read his books. Three National Book Award nominations in the 90’s cements that legacy, and he will truly be remembered as a positive and influential voice for children and teenagers.—Jeff Brown

[1] Mary Ellen Snodgrass, Walter Dean Myers: A Literary Companion (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2006) 5.

[2] Snodgrass, Walter Dean Myers, 65.

[3] Snodgrass, Walter Dean Myers, 27.

[4] Walter Dean Myers, Monster: A Novel (New York: HarperCollins, 1999) 92.

[5] Snodgrass, Walter Dean Myers, 66.

[6] Snodgrass, Walter Dean Myers, 66.

[7] Felicia R. Lee, “Walter Dean Myers Dies at 76; Wrote of Black Youth for the Young,” The New York Times, July 3, 2014. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/04/arts/walter-dean-myers-childrens-author-dies-at-76.html.

[8] Snodgrass, Walter Dean Myers, 66.

[9] Snodgrass, Walter Dean Myers, 65.

[10] Snodgrass, Walter Dean Myers, 66.

[11] Lee, “Myers.”