What better cultural and theoretical aesthetic to interrogate the interplay of black cultural life in the 90s, the present, and beyond than Afrofuturism? The term refers to a broad aesthetic form that employs technology and various artistic forms (it combines elements of science fiction, fantasy, history, magical realism, and Afrocentrism) to link a historical African past with an imagined black diasporic future.

Attempts by black artists to explore diasporic identity, to reconcile the past with the present, and subsequently envision a future where black is situated as subject, are not new. However, this phenomenon was dubbed “Afrofuturism” in 1994 when Mark Dery, a cultural critic and early writer on techno culture, examined recurring features and themes in African American science fiction, music, and art. In his essay “Black to the Future,” as part of an anthology called Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyberculture, Dery interviews writers, such as Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose, in an attempt to explore concerns raised by African Americans writers in the science fiction genre. In the essay, he writes:

Speculative fiction that treats African American themes and addresses African-American concerns in the context of the twentieth-century counterculture–and, more generally, African-American signification that appropriates images of technology and a prosthetically enhanced future–might, for want of a better term, be called ‘Afrofuturism.’

His coinage and definition of Afrofuturism directly relates to science fiction tropes. However, scholars, like Alondra Nelson, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose (among many others), note that the term encompasses varied art forms and genres, as they relate to black culture and its African retentions.

Important to note is that Dery merely assigned a name to this aesthetic; the form itself has been practiced in black diasporic art for years. There is general sense that the features that comprise an Afrofuturist aesthetic are embedded in black cultural DNA; for they hark in every way to a diasporic identity. In an interview, Alondra Nelson, a social scientist who writes on intersectionality of science, technology, medicine, and inequality, says of the term that it “captured what we’d always known about black culture, but it gave us something to call it, to name it…It gives us a tradition and a legacy, where all the pieces sort of fit together.”

Dery’s article is comprised of commentary from Delany, Tate, and Rose, and these three construct the framework of what we know to be Afrofuturism today. Earlier than that, however, Mark Sinker and Greg Tate were generating conversations about black science fiction and its connection to techno culture and music, among others. In 1992, Sinker published an essay, “Loving the Alien” in The New Inquiry, in which he equates historical slavery with alien abduction as represented in literature. Tate wrote a review of David Toop’s Rap Attack called “Yo! Hermeneutics!”, which highlights a science fiction sensibility in black music. According to Nelson, Afrofuturist art, no matter the medium, is imbued with futuristic themes and capitalizes off technological innovation. In the fall of 1998, then a graduate student at NYU, Alondra Nelson and artist Paul D. Miller established an on-line Afrofuturism listserv, and launched Afrofuturism.net in 2000. Both sites were dedicated to science fictions and discussed how the genre addresses a “past of abduction, displacement and alien-nation” and inspires “technical and creative innovations.” Also, in September of 1999, Nelson organized an Afrofuturism forum at NYU, which dedicated conversation to the “future of black production.”

There is no singular definition of Afrofuturism; the aesthetic is as varied and fluid as the cultural identities it explores. To this day, the aesthetic comprises an array of media forms, including, but not limited to, textual, visual, and aural arts. However, at the heart of this aesthetic form lie some artistic and cultural product that 1. examines the past, 2. critiques the present, and 3. “imagines possible futures.” Many works by Afrofuturist artists, in some way, blend elements of the past with the future to assert opinions on sociopolitical and cultural issues concerning black people. With regards to literature, these opinions usually manifest in the dystopian genre. For example, Octavia Butler’s “The Parable Series” (1993-1998), interrogates notions of racial and gender identity in the 2020s. Her depiction of a futuristic society, depraved and plagued by an exacting, ever-widening gap between the rich and poor easily resembles a not-so-far-distant past, and perhaps even the present. Butler, among other black sci-fi writers, also often re articulated traditional African religion and customs in the futuristic contexts of her novels.

Undoubtedly, an Afrofuturistic aesthetic pervades black culture in the 90s. Primarily the music is informed by futuristic sensibilities. Scholars, like Tricia Rose, pointed out how this manifested in the form of technology and sound reproduction. In an interview with Mark Dery, she says, “Digital music technology—samplers, sequencers, drum machines— are themselves cultural objects, and as such the carry cultural ideas.” Musicians, while utilizing aural mechanisms to revamp sound, also incorporated Afrofuturist themes in a visual and lyrical context. Outkast, for example, definitely falls within this extensive lineage of Afrofuturist artists with the albums ATLiens (1996) and Aquemini (1998). Both albums pushed the bounds of production with extraterrestrial sounds and existential, imaginative lyrics.

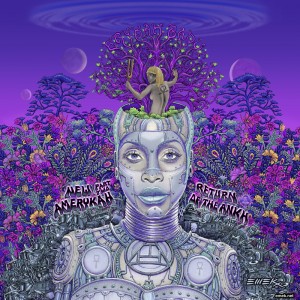

Afrofuturist elements can even be found in Erykah Badu’s video for “Didn’t Cha Know” as it alludes to a liminal space where the subject wanders, simultaneously reaching into the past (allusions to Africa, Kimetics, and Egyptology) and looking towards an uncertain, yet hopeful future. This musical lineage extends even further back, however, to artists, such as George Clinton and Sun Ra, and groups like PFunk, who melded their historically informed visions of the future with jazz and funk sounds. More discussion on the emergence of Afrofuturist aesthetics in science fiction and popular music pre-1990s and 21st-century can be found in John Akomfrah’s 1996 documentary “Last Angel of History.”

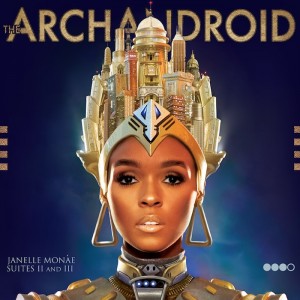

Undoubtedly, Afrofuturist themes pervade most areas of black culture today, perhaps more so than it ever has. Its prevalence is evident from the music of Janelle Monae and Flying Lotus, to the novels of Nnedi Okorafo and Tananarive Due, to the visual and performing arts of Adejoke Tugbiyele and OluShola A. Cole. That its popularity is growing makes sense, since we are still ironing out methods of reclaiming culture, reinventing tradition, and redefining notions of blackness. The questions posed and pondered, even before the advent of Afrofuturism as a theoretical perspective, still remain: How do black people imagine a better future for black people? What does that future look like? And, how do we get there? —Keith Freeman

_____________________________________________

Works Cited

Dery, Mark. “Black to the Future: Interviews with Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate, And Tricia Rose.” Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyberculture . Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1994. 179-222. Print.

Nelson, Alondra. “Introduction: Future Texts.” Social Text. 20.2 (2002): 1-15. Web. 10 November 2015.

Soho Rep. “Afrofuturism.” Online video clip. YouTube. Youtube, 22 Apr. 2006. Web. 05 November 2015.

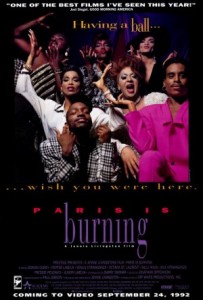

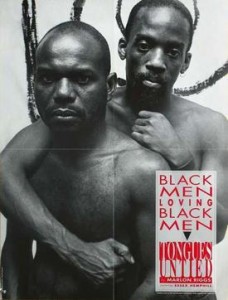

narrative accounts via its director, Marlon Riggs, with fictional vignettes and interpretive poetry that represent a collective yet varied and mutable black, gay identity. The docufilm focuses primarily on gay black men (e.g. Essex Hemphill, Joseph Beam, Craig Harris and Riggs himself) , who also openly and unapologetically confront the ugly heads of racism and homophobia. Scenes of clips from homophobic stand up routines (e.g. by Eddie Murphy) and of the Civil Rights Movements serve to combat negative stereotypes and link the struggles of black, gay men with an historical legacy of resistance. Undoubtedly, “Tongues Untied” is focused and political in its thrust, arguably more so than “Paris is Burning.” Unlike Livingston, Riggs chooses not only to depict men stymied under the weight of white supremacy, but also takes the system to task, illustrating instances of fierce opposition. One such oppositional method is the refutation of silence preluded by the film’s title. Riggs directly challenges this inclination towards silence, not in a way that begets shame (he focuses his critique on a society that promotes and demands speechlessness), but rather one that privileges the power of black, gay men’s voices. Undoubtedly, herein lies the revolutionary mark of “Tongues Untied.”

narrative accounts via its director, Marlon Riggs, with fictional vignettes and interpretive poetry that represent a collective yet varied and mutable black, gay identity. The docufilm focuses primarily on gay black men (e.g. Essex Hemphill, Joseph Beam, Craig Harris and Riggs himself) , who also openly and unapologetically confront the ugly heads of racism and homophobia. Scenes of clips from homophobic stand up routines (e.g. by Eddie Murphy) and of the Civil Rights Movements serve to combat negative stereotypes and link the struggles of black, gay men with an historical legacy of resistance. Undoubtedly, “Tongues Untied” is focused and political in its thrust, arguably more so than “Paris is Burning.” Unlike Livingston, Riggs chooses not only to depict men stymied under the weight of white supremacy, but also takes the system to task, illustrating instances of fierce opposition. One such oppositional method is the refutation of silence preluded by the film’s title. Riggs directly challenges this inclination towards silence, not in a way that begets shame (he focuses his critique on a society that promotes and demands speechlessness), but rather one that privileges the power of black, gay men’s voices. Undoubtedly, herein lies the revolutionary mark of “Tongues Untied.”