In education, conflict over prioritized subject matter taught in schools illuminated larger societal issues of race, legitimacy of cultural expressions and forms of knowledge in America. With the close of the 20th century, several questions continued to emerge: What constituted being an “American”? What does a true American look like, act like, talk like? How does history, and one’s ethnic/cultural background inform one’s place in American society? These questions were (and are) ultimately decided in the schools our children attend – spaces which may operate to reinforce societal norms, options and access to resources.

In education, conflict over prioritized subject matter taught in schools illuminated larger societal issues of race, legitimacy of cultural expressions and forms of knowledge in America. With the close of the 20th century, several questions continued to emerge: What constituted being an “American”? What does a true American look like, act like, talk like? How does history, and one’s ethnic/cultural background inform one’s place in American society? These questions were (and are) ultimately decided in the schools our children attend – spaces which may operate to reinforce societal norms, options and access to resources.

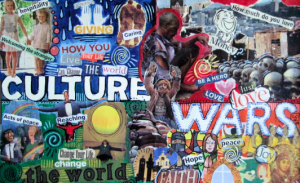

In the 1990s, an interesting series of debates occurred on this subject which were dubbed the “Culture Wars.” These “battles” took place in educational arenas: from classrooms, parent-teacher conferences and staff meetings to school board assemblies, and standardized testing planning sessions. With recognition and attempted incorporation of “minorities,” these debates centered on the question of how school systems educate in ways that relate to students of different cultural backgrounds. One could argue that these conversations were abruptly introduced, ignored and revisited continuously since the legal integration of American public schools in the closing years of the Civil Rights Movement. News articles, academic journal publications, books and even popular TV specials highlighted this phenomenon – in an attempt to answer the aforementioned questions.

This idea of “Culture Wars” is often followed up by the question, “who’s winning?” In a democracy, we all should. Yet these Culture Wars embrace less equality and inclusiveness with more combative and superiority complexes. With Culture Wars at the foundation of our children’s scholarship, this shows just how divided how nation truly is.

Eric Bain-Selbo asserts that these “Culture Wars” originally stemmed from the crucial question: How do we educate our children and young adults? (Bain-Selbo, 2003) The “we” alludes to the entirety of American society, which often is documented to operate under the assumption that citizens of the United States constitute and contribute to one uniform and united culture. This particular culture is cited to stem from America’s inception, and the popular ideals of its founders: life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness, going from rags to riches, equal opportunity, etc.

Henry Louis Gates addresses this assumption by highlighting what is known as the “Great Western Tradition.” This tradition includes patriotic standards, understandings and cultural guidelines in alignment with both the political and socio-economic agendas of the ruling classes in this country (Gates, 1993). This tradition reifies ideas of rationalized manifest destiny, free market capitalism and moral purity of property owners (mainly including White, often Protestant males) – in a prioritized historical narrative deemed heroic and necessary to teach in state public and private schools. From this narrative, all subjects taught are meant to prepare students in their attempts to realize the American Dream. This Dream consists of ultimate access to resources, and the power to make decisions (legislation, voting) that affect everyone moving forward.

In reality, this American Dream did not apply to the majority of peoples of color in this nation. Various ethnic groups, historically and strategically classified as races, struggled to survive and thrive in a society which placed them at odds with those of the wealthiest classes – and each other. These cultural experiences have influenced what could be considered “American” practices and expressions – holding equal weight and importance in contributions to economics, sciences, historical developments, achievements, literature, the arts, etc.

To put it simply, conservatives argued for school curricula to stay as it was, for “Great Western Traditions” to remain the standard. Students from all groups were charged to conform to this ideology, expressed in class lectures, assignments, reading materials and overall subject matter. Gates notes that these conservative public and academic figures considered multiculturalism to be “ethnic chauvinism” (Gates, pg. 174, 1993) These figures clearly contradicted themselves in accusing representatives of other ethnicities of “over-promoting” false histories, to make themselves feel “great” or “worthy of recognition:” especially since presentations of American history often completely omitted the contributions and stories of non-White males.

Those considered to “the right” countered with the multiculturalist argument: the implementation of culturally-relevant pedagogical practices. For educators and researchers of this position, it was important to create learning environments where all children saw themselves reflected in what they were being taught: their families, neighborhoods, histories, languages and forms of knowledge. From this understanding, students could be empowered to draw from these strengths to navigate American society, being productive and able to thrive in all spaces.

Pedagogical theorist, educator and author Gloria-Ladson Billings introduced the 90s to The Dream-Keepers: Successful Teachers of African American Children. She tackles this idea of reversion, and the possibility of African American students needed separate spaces for education, noting that public schools are seemingly already segregated; Non-inclusiveness curriculum vs. African American children.

Furthermore, educators and its administration need to come to a point where they they can stop denying absence of color. “I don’t see race,” is no longer acceptable. You have to see race and culture in order to understand what it is that individual students need. To acknowledge race is a simple means of acknowledging the social, racial, and political hurdles to which one is subjected, and should be only regarded as such, never to use against one. To tackle these Culture Wars, we need cultural acceptance and cultural literacy. Independent of religion or spirituality, (as they are intensely controversial) the simple inclusion of African American history, life, and expression would be a great start in ending the culture wars we witness in education. The public school system needs to create as less dissonance as possible for its minority and unassimilated students.

Ultimately, these “wars” are still waged and fought today. Observations in public school (and even higher academic) environments still reveal the need for greater cultural resources that reflect students’ various experiences. Many educators are still forced to strictly “teach from The Curriculum:” the items mandated by both state and educational officials, preoccupied with standardized testing results. At the same time, a greater number of educators (including many who started these debates in the late 80s/early 90s) have provided solutions. These solutions have manifested in program development strategies, new textbooks, grassroots organizational efforts, and teachers simply “sneaking cultural knowledge in” for their students.

My initial investigations about this make me want to read further on this topic, and draw potential connections to educational practices today.

—Kweku Vassall & Revisited by Tysheira Scribner

Works Cited

Bain-Selbo, Eric. (2003). Mediating the Culture Wars. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Binder, A. J. (2000). Why Do Some Curricular Challenges Work While Others Do Not? The Case of Three Afrocentric Challenges. Sociology of Education, 73(2), 69-91.

(PDF for viewing in our OMEKA entry for this article – very informative)

Gates, Henry Louis. (1993). Loose Canons: Notes on the Culture Wars. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Graff, Gerald. (1992). Beyond the Culture Wars: How Teaching the Conflicts Can Revitalize American Education. New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Ladson-Billings, Gloria. (1994). The dreamkeepers : successful teachers of African American children. San Francisco :Jossey-Bass Publishers,